Perhaps no question hovers more ominously over the history of the Vietnam War in 1967 than this: If the United States and its Vietnamese adversaries had been able to hammer out an acceptable peace deal before the major escalation of the 1968 Tet offensive, hundreds of thousands of lives would have been saved. Was such a peace possible?

For years, pundits and policy makers have speculated on this possibility. Many argue that escalation was irreversible, that the adversaries’ collective fate, as it were, was sealed. But recent scholarship has pointed in a different direction. The prospects of peace were arguably brighter than we once thought. One approach came tantalizingly close to success: the secret talks between Washington and Hanoi that began in June 1967, code-named Pennsylvania.

Pennsylvania began when two French scientists, Herbert Marcovitch and Raymond Aubrac, approached Henry Kissinger, then a Harvard professor, to offer their services as go-betweens to promote negotiations between the United States and North Vietnam. Kissinger had worked as a consultant on the war for the Johnson administration and was eager to do anything he could to ingratiate himself with the president. Aubrac was an old friend of Ho Chi Minh and promised to deliver a message to the aging leader if President Lyndon Johnson had anything new to say. Kissinger referred the proposal to Secretary of State Dean Rusk, with a copy to Defense Secretary Robert McNamara.

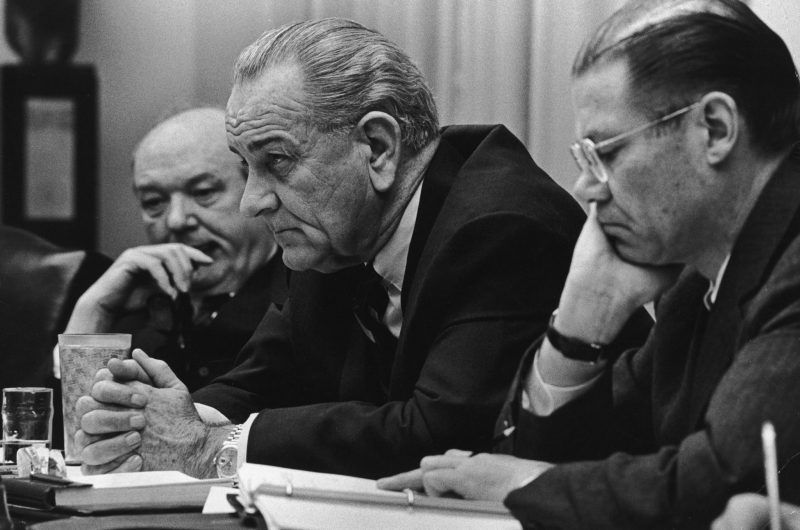

McNamara took the lead in diplomacy during Pennsylvania. Already committed to finding a negotiated way out of Vietnam, he pushed Pennsylvania vigorously at a Tuesday lunch meeting with President Johnson and his key advisers. Johnson was skeptical about any negotiations with the Communists, however, dismissing the French proposal as “just another of those blind alleys that lead nowhere.” But McNamara persisted, and eventually the president relented, allowing his defense secretary to establish contact through Marcovitch and Aubrac, with a view to future peace negotiations — as long as he did nothing to embarrass the United States.

In early July, Marcovitch and Aubrac traveled to Hanoi and presented the Johnson administration’s so-called Phase A/Phase B proposal to the Hanoi leadership. The United States would stop its bombing campaign in return for confidential assurances from Hanoi that it would halt its infiltration into key areas of South Vietnam. Once North Vietnam acted, the United States would freeze its combat forces at existing levels and peace talks could begin. This was a significant departure from Johnson’s previous insistence on mutual de-escalation. The president took the gamble, hoping to placate liberals in Congress and antiwar protesters, who were already planning a huge rally in Washington for that October. Johnson could always resume the bombing if nothing materialized from the contact.

The initial results of Pennsylvania appeared promising. Aubrac and Marcovitch arrived in Hanoi on July 24, 1967, and met with Ho Chi Minh and Prime Minister Pham Van Dong. Ho’s visit with the two scientists was largely ceremonial, but the meeting with Dong was substantive and productive. Dong insisted that North Vietnam could not negotiate while it was being bombed, but he also, surprisingly, indicated that Hanoi would not require the United States to announce the bombing pause publicly, saving Johnson from a potential political problem. If the bombing stopped, Dong assured his guests, negotiations could begin immediately.

A wary Johnson decided to move ahead with a bombing pause, without consulting his South Vietnamese allies or his military command, to get negotiations started. He authorized Kissinger to have Aubrac and Marcovitch tell the North Vietnamese leadership that there would be an additional bombing halt around Hanoi for a period of 10 days beginning Aug. 24, the next scheduled visit of the two French scientists. Hanoi agreed that this was a productive change in the United States’ position and a positive outcome of the Pennsylvania contact.

For the first time in years, it appeared that the two sides were serious about negotiations. Chet Cooper, an aide to W. Averell Harriman, Johnson’s “peace ambassador,” called Pennsylvania the last best chance for peace, knowing that the war was likely to escalate otherwise.

On the day that Aubrac and Marcovitch were to leave Paris for Hanoi, United States aircraft flew more than 200 sorties against North Vietnam, more than on any previous day of the war. The official explanation for the poor timing of the bombing missions was that the attacks had already been scheduled for earlier in the month but had been delayed by bad weather. Once the weather broke on Aug. 20, the bombing resumed according to protocol and lasted four days.

Hanoi publicized the new attacks, claiming that Johnson had used the proposed bombing pause as a diversion while he actually escalated the war. Johnson denounced these claims, but he could not hide the fact that he had indeed approved an escalation to the bombing just two days before it began, on Aug. 18, and had used the weather delay as a convenient cover for his actions.

Perhaps the president believed that the United States had to hit all available targets before the pause in case it did not get another chance. Johnson even approved one target on the grounds that if talks with Hanoi materialized, he would not want to approve the site later. All along, Johnson had been skeptical about the Pennsylvania contact. He claimed later that the United States should never have held back on the bombing just because “two professors [were] meeting.” Johnson was absolutely certain that the bombing was hurting the North Vietnamese and wanted to keep “pouring the steel on.”

But Johnson never considered how increased bombing raids would play in Hanoi, and that says much about how American leaders went to war in Vietnam. Even after dozens of failed secret peace contacts before Pennsylvania, the Johnson administration could not see that an apparent escalation in bombing on the eve of a possible peace mission was not a formula for diplomatic success.

The bombing raids not only killed the secret peace talks but also played directly into the hands of the hard-liners on the Military Commission of the Political Bureau in Hanoi, who had consistently argued against negotiations of any kind. Rejecting the views of some in the Foreign Ministry, Hanoi’s hawks now had all the evidence they needed that the United States was not serious about negotiations. The top leadership concluded that North Vietnam had no choice but to endure the bombing while simultaneously trying to erode Washington’s ability to remain in South Vietnam.

North Vietnam increased its infiltration into South Vietnam in preparation for a major escalation of the war in early 1968. Gen. William Westmoreland sensed this buildup and asked Johnson to increase United States troop levels in Vietnam. The number of Americans fighting in Vietnam rose to over 500,000 just a few months after Pennsylvania’s failure.

The talks failed because political and military leaders in Washington and Hanoi were afraid to take a chance on peace. Hard-liners in Hanoi won the day after Pennsylvania’s collapse. They pushed for a quick military escalation in South Vietnam, erroneously believing that the planned Tet offensive would lead to a general uprising that would topple the Saigon government and force the United States to withdraw all of its troops. Johnson, in contrast, was desperately trying to keep his options open by escalating the bombing just before a pause, but in the end he actually narrowed his choices.

Trying to placate both antiwar members of Congress and his generals, who wanted a wider war, Johnson tried to find a middle ground when there was none. He never fully committed to negotiations and, believing that the war had to be fought with costs and risks in mind, unsuccessfully juggled competing interests and ideas. Of course, Johnson also never consulted his allies in Saigon about the secret peace talks, which would have added a dimension of complexity to any agreement.

Ironically, within nine months of Pennsylvania’s failure, the United States was engaged in negotiations with North Vietnam and the National Liberation Front, also known as the Viet Cong, that would eventually lead to a unilateral American military withdrawal and a cease-fire in 1973 that allowed 10 infantry units of the North Vietnamese Army to stay in South Vietnam. The failure of the last best chance for peace shaped the war for years to come.

Robert K. Brigham is a professor of history and international relations at Vassar.