On Friday 14 April, a team of west Africa-based journalists will arrive in Cameroon, one of the most oppressive countries on the continent. Our three colleagues will be there to conduct an “Arizona Project”, named after the events in 1976 when journalists in the US state came together to finish the story that a murdered colleague had been working on. Their motto – “You can kill a journalist, but you cannot kill the story” – applies now more than ever, especially in Cameroon.

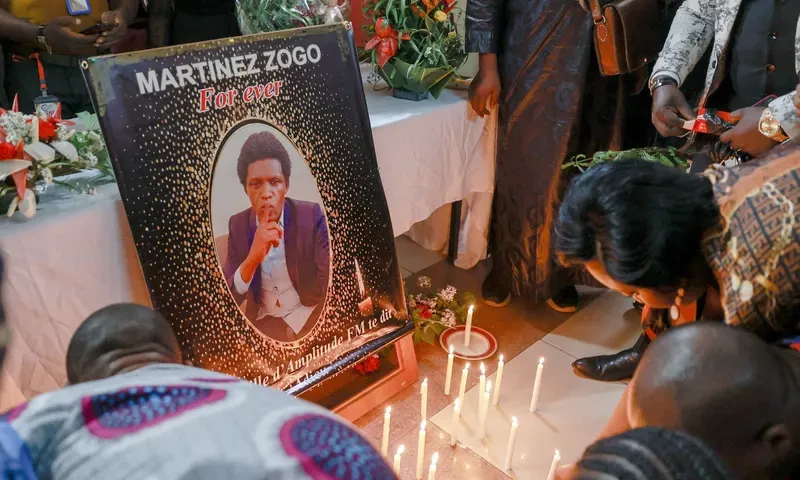

What was the story that killed Martinez Zogo, the 50-year-old radio journalist, whose mutilated body was found on 22 January in a suburb of the capital Yaoundé, days after he had been abducted by masked men outside a police station in the city?

What little is known is that Zogo’s story concerned an alleged embezzlement case involving the regime-friendly media tycoon Jean-Pierre Amougou Belinga. Belinga was arrested in connection with the murder on 6 February, and on 4 March was officially charged with complicity in torture. Belinga has denied guilt.

This already points to a big difference between events in the US in 1976 and Cameroon in 2023. First, the Arizona journalists would have been able to conduct their investigation with some protection from law enforcement.

The organised crime figures who murdered journalist Don Bolles might have killed once, but police came out in full force to prevent any repeat. In Cameroon, Zogo touched on state corruption, which might imply state-connected forces in his torture and murder. Also, unlike in Arizona, journalists have been murdered in Cameroon before; each had been investigating – or denouncing – embezzlement of state funds enriching a kleptocratic elite.

Crucially, and in contrast to Arizona, a blanket of silence has now descended on Cameroon, terrifying and muzzling citizens and journalists. “We are all afraid to report and our sources are all afraid to talk”, said one Cameroonian member of Naire, the Network of African Investigative Reporters and Editors, which is running this Arizona Project in partnership with Zam magazine. This is why an international team will now pick up the threads of the story Zogo left unfinished.

Sadly, Cameroon is not the only African country experiencing increasing oppression of media and civil society. In the same week that Zogo’s body was found, another journalist was killed in Rwanda, and a human rights lawyer was gunned down in Eswatini. In 2022, close to 60 journalists in Africa were assaulted, imprisoned, abducted or forced into exile.

In practically all these cases, even when arrests are made – which are often temporary – impunity reigns.

No one was ever arrested for the murder of my colleague, Ahmed Hussein-Suale. He was shot dead in my country, Ghana, in 2019, during an investigation of – among others – a politician, Kennedy Agyapong, for corruption. Just before Ahmed was killed, Agyapong exposed him and called for violent action against him on television. He later said he will “never regret showing the pictures” of the undercover journalist.

Agyapong is also behind several actions against me and my media house, Tiger Eye PI, for which Ahmed worked. Having already called for me to be hanged, Agyapong went on national radio and to call me a murderer, a blackmailer and a thief (among other things). His behaviour attracted international condemnation but, more worryingly for me, in the defamation case I brought against Agyapong in the high court, the judge, Justice Baah, was sympathetic to Agyapong in his verdict, finding none of the politician’s insults defamatory and even repeating allegations of criminal conduct against me, as if I were the one on trial.

Agyapong is now a presidential candidate in Ghana. It is in this culture of impunity that I have recently set up the Whistleblowers and Journalist Safety International Centre (WAJSIC) as a shelter organisation. It is already oversubscribed.

The persistent action against me and my colleagues in many African countries is illustrative of the climate we work in. In Senegal, Pape Alé Niang has recently been arrested, detained and harassed for corruption reporting. Theophilus Abbah in Nigeria has been the target of a frivolous lawsuit – a so-called Slapp suit of the type increasingly used against journalists by the rich and powerful. The list goes on.

We as Naire, in partnership with Zam, are conducting the Cameroon Arizona Project in the hope that the world will take note of what individuals such as Agyapong and kleptocratic and oppressive politicians are doing in our countries. They should be investigated, held to account and subject to sanctions. Just limiting their travel, shopping trips to London and New York and their use of stolen money to buy Mediterranean villas will help hearten us as journalists and citizens who yearn for democracy, transparency and good governance in our countries.

We hope that this article, along with the Arizona Project, will focus the attention of international media and civil society on our need for action and support. We hope to publish the results of the Arizona investigation on the Zam website and in partner media worldwide and that members of the media, civil society organisations, NGOs, academic institutions and researchers who want to follow up on the team’s findings, will help to alert global players to our plight and our requests for support.

Anas Aremeyaw Anas.