Eight weeks ago, I was among those celebrating Sadiq Khan’s election as the new mayor of London. The victory felt symbolic: Mr. Khan, a state-school-educated son of a bus driver who immigrated from Pakistan, had been given the largest personal mandate of any politician in British history. I am the same age as Mr. Khan and I’m also a state-educated son of Pakistani Muslim immigrants, and so his win felt especially validating for me. London had sent a message that it was open, tolerant and welcoming. This city, where I have lived for almost 20 years, was really a place I could feel comfortable and call home.

Thursday’s Brexit vote was a bracing reminder that London is not England. While nearly 52 percent of Britons voted to leave the European Union, London voted overwhelmingly to remain. Twenty-eight of the city’s council areas voted Remain, while just five — all outer boroughs — voted Leave. I live in Hackney, a neighborhood in north London where more than 78 percent of voters chose to remain in Europe — just behind Lambeth, in central London, for the most Europhilic place in the country.

In the days since the result, I have visited London bars, coffee shops and restaurants. The prevailing reaction has been shock and disorientation. It reminds me of the days after the death of Diana, Princess of Wales — that sense of grief and a need to process what just happened. Everywhere I went people were discussing the result of the vote and its consequences: The Turkish waiter in my neighborhood cafe was reassuring an old Turkish man, who looked shellshocked, that he didn’t need to worry. The bartender in the coffee shop was relating the latest plunge in the stock market to the woman who was buying a latte.

In the days since the result, I have visited London bars, coffee shops and restaurants. The prevailing reaction has been shock and disorientation. It reminds me of the days after the death of Diana, Princess of Wales — that sense of grief and a need to process what just happened. Everywhere I went people were discussing the result of the vote and its consequences: The Turkish waiter in my neighborhood cafe was reassuring an old Turkish man, who looked shellshocked, that he didn’t need to worry. The bartender in the coffee shop was relating the latest plunge in the stock market to the woman who was buying a latte.

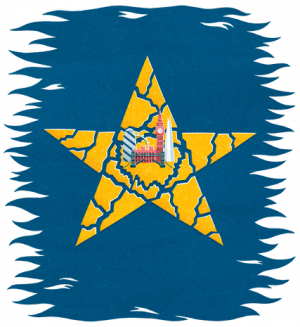

For many of us, Thursday’s verdict is a reminder that we live in the London of Sadiq Khan but also the Britain of Nigel Farage, the leader of the nationalist U.K. Independence Party. While the referendum was technically about the European Union, the real issue was immigration, with the Leave campaign pushing xenophobic propaganda. Since the vote, there seems to have been a surge in racist incidents.

Not everyone who voted Leave is a racist, but it feels as if all the racists voted Leave. “We’re British, we don’t want all the other people — we just want us,” a middle-aged woman told a reporter for Sky News.

“It’s not about trade or Europe or anything like that,” a man in Yorkshire, in the north of England, told another news program. “It’s about immigration. It’s to stop the Muslims from coming into this country. Simple as that.”

Statements like these suggest that the referendum has emboldened those who yearn for an England before mass migration. When Daniel Hannan, a pro-Leave member of the European Parliament from the Conservative Party, was discussing the fallout from the vote on BBC radio recently, he used the words “phased repatriation.” He was referring to the return of rights from Europe to Britain, but anyone who grew up here in the 1970s and ’80s as the child of immigrants knows the word “repatriation” is freighted with ugly implications. It conjured up a frightening time when the far right was on the rise and immigrants and their children feared we would be encouraged or forced to return to countries that felt foreign but that others insisted were our true homes.

Britain is in a culture war in which those who are younger, better educated, more traveled and living in cities see the world very differently from the rest of the nation. It doesn’t surprise me that nearly 175,000 people have so far signed a petition demanding that London declare independence from Britain and apply to join the European Union. This futile gesture symbolizes how the city feels isolated from so much of the rest of the country. I may feel home in London, but the rest of Britain increasingly seems like a foreign country.

This sense of foreignness isn’t just about race, religion or nationality. Like many Londoners, I moved here from somewhere else. I grew up in Luton, a gritty postindustrial town just an hour drive from Hackney. Luton has a sizable Muslim population, and in recent years Eastern Europeans have settled in the town, too. On Thursday, 56 percent of voters in Luton chose to leave the European Union. My hometown also feels part of this foreign country.

London has a population of about 8.5 million and more than a third of that is now foreign-born. The city encompasses more than 270 nationalities and 300 languages. I live here because it encourages and welcomes hyphenated identities. I can be Pakistani, Muslim, British and European at the same time; my wife can be Scottish and British. The vote seems to have been a vote against multilayered identities. That alarms me. My family and I — my white wife, who was born in Scotland to English parents, my mixed-faith, mixed-race daughter — can feel at home only in places that allow a more complex identity.

Last Thursday I stayed up all night to watch the election results. When my wife woke up, I told her that Britain had voted to leave the European Union but that London and Hackney had voted overwhelmingly to stay in. She started crying. “This feels like a nightmare,” she said. “We can’t ever leave London.” The streets of London still feel familiar and safe, like home. But I worry about what lies beyond.

Sarfraz Manzoor, a journalist and broadcaster, is the author of the memoir Greetings From Bury Park.