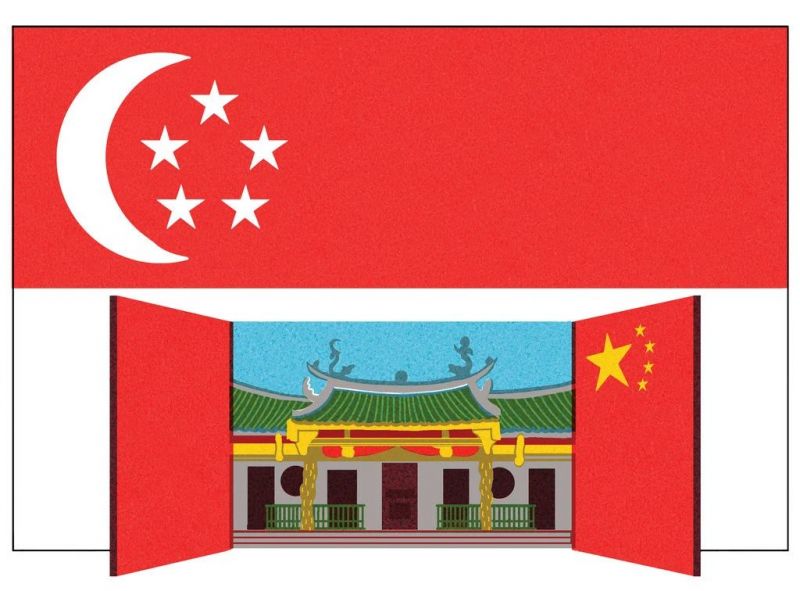

Festooned with red lanterns and banners bearing auspicious messages, the ornate façade of the 19th-century Thian Hock Keng temple in downtown Singapore seems even more flamboyant than usual. The temple is readying itself for its busiest time of the year: Over the next few weeks thousands of worshipers will make offerings and pray for a favorable Chinese New Year. It’s a time when even the least conscientious of temple-goers, like me, make an effort to maintain the customs that link them to their heritage.

Such a classically Chinese setting may seem an unlikely place to start questioning one’s traditions, but to be in Singapore today means to challenge conventional ideas of Chineseness. As China rises on the world stage, it is exporting its notions of Chinese culture and ethnicity, creating new tensions within Chinese communities abroad. In Singapore, Chinese people used to be called zhongguo ren or hua ren interchangeably: The small distinction between the two terms — the former relating to people with Chinese nationality or born in China; the latter to anyone ethnically and culturally Chinese — was considered artificial. But subtle divisions of this kind have now become the crux of what it means to be Chinese here.

Three-quarters of Singapore’s people are ethnically Chinese, most descendants of Hokkien-speaking immigrants from Fujian Province in southern China who came to the island in the first half of the 19th century, when it was a British settlement. Malays and Indians, both indigenous and immigrants who also arrived in the 19th century, have long formed important communities in the territory. But it is the predominance of the ethnic Chinese that was crucial to Singapore’s formation in the first place.

In 1965, Singapore broke off from freshly independent Malaysia as a direct result of bitter disputes over the preservation of rights for ethnic Chinese and other minorities in the new Malay-dominated nation. (The two territories previously were part of a loose federation.) Today, this tiny Chinese enclave has a G.D.P. per capita about five times that of its far larger, resource-rich neighbor.

But it is precisely this upward economic trajectory that has begun to raise questions about what it means to be Chinese in modern Singapore. In 2013, the government published a white paper that laid down plans for sustaining economic growth and increasing the population from about 5.3 million to 6.5 to 6.9 million by 2030. In an already densely populated island with limited space for new construction, the plan sparked widespread debate and unprecedented public protests: Given Singapore’s low birth rate, this increase in numbers would have to be fueled by immigrants — largely, it was presumed by many, from China.

On the face of it, few cultural mergers could be more seamless. Singapore’s multilingual educational system treats Mandarin as a de facto second language after English. Almost half a century ago, the country adopted the simplified system of writing Chinese that is used in mainland China, rather than the complex forms from Hong Kong and Taiwan. In the late 1970s, the government launched a Speak Mandarin campaign to limit the use of various Chinese dialects. Familiarity with Chinese culture is presumed from similarities in food and shared customs rooted in Confucianism, Buddhism and Daoism.

Yet a chasm remains between the Chinese of Singapore and their mainland counterparts, divided by contemporary social values and the very language that is supposed to bind them all.

Singapore’s lively Internet media and online forums reveal a pattern of prejudice toward immigrants from China. Mainlanders, Singaporeans often complain, are rude and uncivilized: One recent story that caused outrage on open portals such as The Real Singapore and STOMP, the Straits Times’ “citizen-journalism website,” centered on a “PRC woman” relieving herself on the otherwise spotless floor of a subway station. Chinese immigrants, for their part, are frustrated by what they perceive as aloofness, as well as a lack of fluency in standard Mandarin, or putonghua, among Singaporean Chinese — proof that their island cousins are not truly Chinese.

The result of this tension is an uneasy two-way xenophobia, with each side accusing the other of racism even though both are Han Chinese. Predictably, this has led to a reassertion of cultural identities. In shops, public transport and the island’s famous hawker centers, Singaporean Mandarin — a heavily accented strain of putonghua, which includes idiosyncratic vocabulary and a smattering of words imported from other dialects as well as English — shows no sign of becoming standardized, despite many TV and radio programs featuring classic mainland-inflected pronunciation. Local dialects, especially Hokkien, still thrive. Although schools are required to teach Mandarin to ethnic Chinese students, a sizable proportion of Singaporean Chinese, mainly from affluent classes, remain more comfortable in English than Mandarin.

The visible influence of China in the everyday lives of Singaporeans has sharpened their sense of identity as Singaporean rather than as the descendants of Chinese mainlanders. If the Chinese of Singapore once defined their Chineseness in opposition to Malaysia, today they are distancing themselves from China. As one Singaporean Chinese friend of mine told me before heading to Japan for work this past autumn, at the height of tensions between China and Japan over the Diaoyu/Senkaku islands, “I just need to make sure they know I’m Singaporean, not Chinese.”

But at the Thian Hock Keng temple, as I join other worshipers in preparing traditional offerings of incense, it’s hard for me to think of my surroundings as “not Chinese.” Most Singaporean Chinese I speak to (in Mandarin) still refer to themselves as hua ren, or linked to the customs and traditions of China. Yet in harnessing its ancient heritage to a newer national identity, the Chinese diaspora in Singapore has created a hybrid culture that questions the idea of a single Chinese identity.

Tash Aw is the author of three novels, including, most recently, Five Star Billionaire.