In September 2015, the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles acquired the first photographs ever taken of Palmyra, the great trading oasis in the heart of the Syrian desert. Louis Vignes was a young lieutenant in the French navy whose interest in photography earned him a place on a scientific expedition to the Dead Sea region in 1863. The twenty-nine photographs he made of Palmyra during his visit in 1864 (including two panoramic shots) were finally printed in Paris by the pioneering photographer Charles Nègre (who had taught Vignes) between 1865 and 1867.

With a history that extends back nearly four thousand years, Palmyra has risen and fallen many times. Its original name was Tadmor, which probably meant “palm tree,” an indication of the site’s renowned fertility. Both the Bible and local legend credit the city’s foundation to King Solomon in the tenth century BCE, but in fact it is already mentioned in Mesopotamian texts a millennium earlier. A spring and a wadi, or dry river bed, provided the settlement with water, making it a welcome stop for travelers and traders on the road between Central Asia and the Mediterranean Sea.

The population, almost from the outset, was a mixture of Semitic peoples from surrounding areas: Amorites, Aramaeans, Arabs, and Jews, who developed a distinctive Palmyrene language and a distinctive script expressive of their distinctive cosmopolitan culture, which drew from Persia, Greece, and Rome as well as local tradition. The city expanded greatly in the Hellenistic period, in the wake of Alexander the Great (fourth century BCE), and again during the Roman Empire. Its most impressive archaeological remains date from the first and second centuries CE, when the expansion of the Roman Empire streamlined the trading networks that gave Palmyra life. Some 200,000 people may have made their home in the oasis, which was granted a political independence unusual under Roman rule; Emperor Hadrian, who visited in 129 CE, declared it an independent city-state.

The weakening of Rome and the rise of Sasanian Persia in the third century CE cut into Palmyra’s share of trade between Asia and the Levant. For a brief moment, from 271 to 273, the local queen Zenobia managed to hold off both the Persians and Rome to claim an empire of her own, but in 273 the Roman emperor Aurelian conquered the city, looted its temples to decorate his own Temple of the Sun in Rome, and razed its residential quarters. In 303, Emperor Diocletian supplied Palmyra with its own Roman fortress, a walled camp to house a permanent garrison of soldiers. Just two centuries later, in 527, the Byzantine emperor Justinian further reinforced the city walls.

Christianity became the dominant religion in Palmyra after Aurelian’s conquest; Islam arrived in 634, when the city had been reduced to a village within the walls of Diocletian’s camp. Under the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates, the city, now renamed Tadmur, grew and prospered despite its tendency to rebel against any form of centralized authority and the animosity of nature: earthquakes caused widespread destruction in 1068 and 1089. In 1230, with the Crusades menacing from abroad and the death of Saladin creating turmoil locally, Al-Mujahid Shirkuh II built a castle on the summit of the mountain overlooking Palmyra, but in 1400 the city fell to the Central Asian warlord Timur—Tamerlane—who not only destroyed it yet again, but also shifted the caravans to other routes. Palmyra’s few remaining residents huddled within the walls of the precinct surrounding the ruined ancient Temple of Bel.

These are the conditions that visitors like the Roman nobleman Pietro della Valle found in the early seventeenth century, followed by many other European visitors, including Robert Wood and James Dawkins in 1751, Lady Hester Stanhope in 1815, and Louis Vignes in 1864. Nineteenth-century visitors to the site could, and did, carry off sculpture and inscriptions from the surrounding ancient cemeteries with relative ease, to grace public museums and private collections.

Palmyra expanded again in the early twentieth century as the Great Game began to play out on Mesopotamian soil, now an emporium that welcomed motor traffic as well as camel caravans. By 1932, Syria’s general director of antiquities, the Frenchman Henri Arnold Seyrig, had convinced the residents of old Tadmur to move out of their homes among the ancient ruins and into a new village especially constructed for them by French builders. Archaeological investigation of the site began immediately afterwards, and Palmyra adapted to the tourist trade with additions like the Hotel Zenobia, built in 1900 right next to the Temple of Baal Shamin.

The Lebanese war that raged between 1975 and 1990 and the Syrian civil war of the past four years have damaged or destroyed many of the monuments that Vignes records in his photographs. The worst destruction, certainly, was inflicted between June and September of 2015 by the militants of the Islamic State, who first tortured and killed the eighty-one-year-old site director Khaled el-Assad before beheading him and hanging his body from a column. Then they set to work obliterating the ancient buildings amid accusations of paganism and idolatry.

These acts of destruction, like those of Aurelian and Timur, were deeds of pure brutality, a distressingly recurrent theme in the story of humankind. Yet Palmyra has also suffered destruction in the lofty name of knowledge: it was twentieth-century archaeologists, not Islamic fanatics, who obliterated old Tadmur Village, and many other structures, like fortification walls, that dated from post-classical times. These places and these structures had their own tales to tell; in them, sometimes for centuries, people lived out their lives, built their families, gathered their memories. And thus a sensitive soul (identified only as Stenhouse 1) on Palmyra’s Trip Advisor website found time recently to mourn not only the ruined temples of Bel and Baal Shamin, UNESCO Heritage buildings exploded by the fanatics of the Islamic State, but also a more recent piece of Palmyrene history, the once grand old Hotel Zenobia, turning his thoughts all the while to the people who had once worked there. In six brief sentences, Stenhouse 1 says it all:

There is nothing left of this hotel now. I hope that the lovely staff who welcomed us there are safe and well. Once peace returns, Palmyra will rise again. It’s a fascinating place and this hotel will be rebuilt. It had the most incredible location. You could literally breakfast in the ruins. April 1, 2016.

The great Temple of Bel was surrounded in Imperial Roman times by an impressive ornamental perimeter wall that divided its sacred precinct from the workaday world. Part of the temple became a mosque in the eighth century. In 1132, the temple and its courtyard were turned into a fortress, inside which the entire village, by then identified by Palmyra’s primordial name, Tadmur, huddled for protection.

In the background of this photograph we see the ruins of the castle rebuilt by the seventeenth-century Emir Fakhr-ad-Din, a Druze warlord who spent five years of his life as an exile in Italy before returning home to defy the Sultan and create his own fiefdom in Syria. The flat-roofed mud-brick houses of Tadmur dominate the foreground.

The interior of the precinct was surrounded by a colonnade, vividly described by the English visitor Charles Addison, who visited Palmyra a decade before Louis Vignes:

This large area measures about two hundred and twenty-five yards each way, and the remaining columns that surround it have all a projection from the shaft for statues, and in some the iron to which the feet of the statues were fastened is plainly visible. All of the columns of the porticoes have this projection, and if they were all furnished with statues, what hundreds and thousands there must have been in the place—and whither can they have been carried? Of this portico the greatest number of columns exists on the west side; they are thirty-seven feet in height, and rising above the humble mud huts of the village and here and there supporting fragments of the architrave and sculptured cornice that once rested upon them, they present a striking contrast of the magnificence of bygone times with the poverty and meanness of the present day. (Charles Greenstreet Addison, Damascus and Palmyra: A Journey to the East. With a Sketch of the State and Prospects of Syria under Ibrahim Pasha, Philadelphia: Carey and Hart, 1838, p. 167)

Gertrude Bell, who camped at Tadmur/Palmyra in 1900, called this structure the “Saracen Gate.” Charles Addison laments that “The ancient majestic portal has been concealed by a barbarous square tower built up against, it, probably by the Saracens, when the citadel was converted into a fortress.” (Damascus and Palmyra, p. 166). The “barbarous square tower” has been hastily built from pieces of the ruined temple precinct, including many ancient column drums turned on their sides, easily visible in the photograph. The desert in the background is dotted with Palmyrene tower tombs. The site itself looks just as lonely as it did to Addison in the 1830s:

The population of the village of Tadmor appears to be very scanty; we have not seen more than two or three male inhabitants since our residence in the place, and these are generally idling under the great gateway; the women we have hitherto seen have a dirty and repulsive appearance, and many of the little children are quite naked. (Charles Greenstreet Addison, Damascus and Palmyra: A Journey to the East. With a Sketch of the State and Prospects of Syria under Ibrahim Pasha, Philadelphia: Carey and Hart, 1838, p. 162)

The gate was not directly targeted for destruction in 2015 and survives. The village was razed in 1932.

Today, the deserted tracts of land beyond the Temple’s precinct walls have been covered by the modern settlement of Tadmur. To the left of the standing columns we can see the stub of another column embedded in a villager’s house. The precinct wall shows many signs of later repairs and reinforcements, with irregular blocks of stone and rubble, not to mention the mud-brick masonry of the villager’s houses, all removed in the 1930’s. These columns have survived the destruction of 2015.

Ancient worshippers entered the Temple of Bel through this monumental gate of the second century CE, rising high above the village houses that had entirely overtaken the structure in later centuries. As Charles Addison complained in 1835:

Proceeding up the principal lane or pathway of the village, portions of the ancient pavement of large square flat stones are discoverable, and directly in front rises the great temple with its grand and lofty portal and tall fluted columns divested of their brazen capitals. It is surrounded and disfigured by the mud huts of the village, through the interior rooms of which you are obliged to walk to get to the different parts of the building. (Damascus and Palmyra, pp. 167-168).

We can see the holes in the gate’s roughly carved capitals where their gilded bronze sheaths were once attached. The slightly flaring shape of the stone cores confirms that the columns must have been Corinthian.

This section of the temple is the only part to have survived the explosions set off in 2015.

Looking over the flat rooftop terraces of Tadmur, we can see part of the colonnade enclosing the precinct of Bel on the left and the temple itself on the right, preceded by its monumental portico. The small holes in the wall of the temple’s cella (central chamber) show attempts by later generations, no longer believers in Bel, to dig out and recycle the bronze clamps that linked together each of the temple’s huge stone blocks. This building was largely destroyed by explosives in 2015. Only two columns and a section of the portico survived.

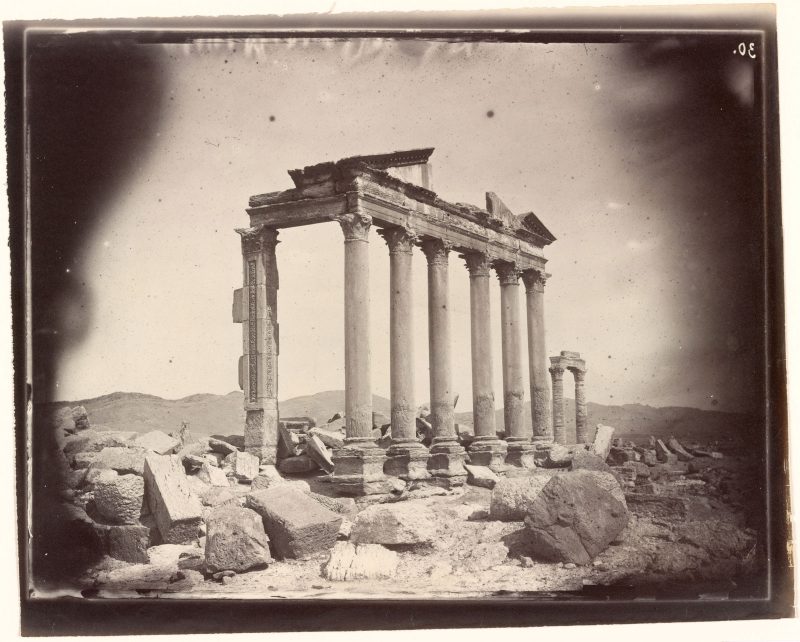

Vignes is standing close to the wall of the temple precinct to take this shot. The elaborate Corinthian capitals of the colonnade are so delicately and airily carved that we can see through the coil of a curling acanthus leaf atop the leftmost column. The temple itself can be seen in the background to the left, and a stretch of the precinct wall to the right. These columns survived the explosions of 2015.

The temple’s columns look fat and stubby because they are partially buried. For the same reason, the statue brackets that are so characteristic of Palmyra protrude from the columns just above ground level. In 1900, after the site had been cleared, the Hotel Zenobia was built right next to the temple to accommodate a growing tourist trade; Agatha Christie, married to archaeologist Max Mallowan, was a frequent guest.

This small, stately temple was reduced to rubble by explosives in 2015.

Palmyra’s Triumphal Arch was built during the reign of the Roman emperor Septimius Severus (reigned 193-211 CE) to create a graceful transition between the main street of Palmyra and the short road from the city to the precinct of Bel. Here the Great Colonnade that lines the thoroughfare, built over the course of the second and third centuries CE, bends at a 30° angle. The three arches accommodate wheeled traffic in the center and pedestrians on the two sides of the road. Although the Arch has no religious significance, it was destroyed in successive explosions lit by the Islamic State in 2015. Much of the stonework survives in good enough condition for the structure to be rebuilt from its original materials. The rest of the Great Colonnade still stands.

The dramatically sited castle of Fakhr-el-Din dominates the background behind a view of the western portion of the Great Colonnade. Like its temples, Palmyra’s streets were lined by columns outfitted with protruding brackets to hold bronze statues. In many cases, inscriptions carved into the column shafts beneath the brackets still reveal the identity of the honoree. The statues are long gone, melted down for their bronze. These unfluted streetside columns are much more badly weathered than their elaborately carved and fluted counterparts on Palmyra’s temples, because they have been made of softer, cheaper stone. The carving of capitals and brackets is rough and ready, the stuff of everyday life. The columns of the earliest portions of the Colonnade, begun before 158 CE, are made from stacks of several cylindrical drums. The later portions, completed about fifty years later, have columns composed of only three pieces each.

In the background to the left, we can see the pediment of the temple-tomb nicknamed the Peristyle, or Tomb No. 86, which Vignes also photographed close up. It probably dates from the time of Queen Zenobia, that is, the late third century CE.

The ornamental arch in the center of this photograph gracefully resolves the problem posed by ranges of columns pitched at different heights, each coordinated with the proportions of the building that once stood behind it.

In the right-hand background, we can see the Citadel of Fakhr-ad-Din and an impressive scatter of Palmyra’s distinctive tower tombs.

The Colonnade sustained damage in 2015, but only the Triumphal Arch was specifically targeted for destruction by the Islamic State.

Here we can see clearly that the Temple of Bel, dedicated in 32 CE, was built on an artificial mound, or tell, created by the ruins of a previous temple dating from Hellenistic times, probably some three hundred years earlier. The enclosure wall in the left foreground is made up in part of column drums taken from the ruins of the temple itself or from other structures. The temple precinct, when Vignes took this photograph, was also the walled village of Tadmur.

The best-preserved stretch of the precinct wall of the Temple of Bel is the southwest corner, with its ornamental pilasters breaking up the monotony of the imposing wall and making what is in fact a bristling fort look like nothing more than an elegant temple enclosure.

A toppled column in the middle of the road emphasized the fact that this view of Palmyra’s main street is the photograph of a grand ruin. The Triumphal Arch rises in the background.

In his photograph, Vignes juxtaposes this imposing second-century tower tomb with the seventeenth-century fortress of Fakrh-ad-Din. The structure was created in 103 CE to serve as the tomb of the Palmyrene aristocrat Marcus Ulpius Elahbelus, who became a Roman citizen, and his brothers Manai, Shekhaiei, and Malku. Elahbel’s first two names are identical to those of the reigning Roman emperor, Marcus Ulpius Traianus—Trajan, and presumably express his loyalty to his newly adopted city and its ruler.

After Gertrude Bell visited Palmyra in 1900, the partly ruined tower was reconstructed to its full height, but the Islamic State destroyed it by explosion in 2015.

The Tomb of Marcus Ulpius Elahbelus—Elabel—is the second tower from the left in this panoramic view of Palmyra’s Valley of the Tombs, located to the southwest of the city. As with most ancient Mediterranean settlements, the graveyard was located outside the city walls to ensure that the ghosts of the deceased would not bother the living. The two best-preserved tombs, of Elabel on the left and Iamblichus on the right, were pulverized by the Islamic State in 2015.

This panoramic view traces the Great Colonnade from the western wall of Palmyra to the precinct of Bel on its tell to the east of the city. The two most prominent buildings in the landscape, the Temple of Bel in the background of the left-hand image, and the Temple of Baal Shamin in the background on the right, are the two buildings that were deliberately destroyed by the Islamic State in 2015.

This array of sandstone tower tombs stood along the main road from Palmyra to Homs and Damascus, to increase the chances that a passerby would read the epitaphs of the deceased and say a prayer on their behalf. Each belonged to a Palmyrene family. The interiors were richly painted and contained statues of the family members interred there as well as the stone boxes that served as their graves. The two best-preserved tombs were obliterated by the Islamic State in 2015.

This magnificent tomb from 83 CE was built by the client ruler Yamlichu of Emesa (Iamblichus) as a dynastic monument, and blown up by the Islamic State in 2015.

A close-up view of the tower tombs at the foot of Umm-al-Bilqis Hill to the southwest of Palmyra.

Each one contained elaborately decorated chambers that could hold hundreds of the small boxes to which wealthy Palmyrenes consigned their dead.

Built between 293 and 305 CE, the Camp of Diocletian was a Roman military settlement at the opposite end of the Grand Colonnade from the Temple of Bel, and like the Temple of Bel it was situated on a low hill and surrounded by a wall. Its two main streets ran perpendicular to one another and met at a four-way gate, the Tetrapylon. Like Palmyra’s main street, they were adorned with colonnaded porticoes.

This elaborately carved temple to the northwest of Palmyra’s Grand Colonnade is a tomb from the late second or early third century, either dating from the time of Queen Zenobia or from the restorations of the city by the Roman Emperor Septimius Severus. It has been nicknamed the “Peristyle,”although technically it is a peripteros, a structure surrounded by a colonnade, rather than a peristyle, which is a colonnaded enclosure. It has apparently survived the Islamic State’s depredations of 2015. The man who leans against a column is the only trace that Vignes provides of the people who inhabited Tadmur Village when he paid his visit to Palmyra. The Peristyle was restored in 1970 and seems to have survived the attacks of the Islamic State in 2015.

Here Vignes provides a magnificent overview of Palmyra that extends from the western end of the Grand Colonnade to the precinct of Bel in the east. In the subsequent four decades of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, the oasis would once again gain in importance as a stopping point for caravans, and this bleak, windswept panorama would become the site of a modern Syrian town with a population of more than 50,000. The Islamic State destroyed a number of this panorama’s most conspicuous monuments in 2015, the Temple of Bel the most conspicuous of all.

Ingrid D. Rowland is a Professor at the University of Notre Dame’s Rome Global Gateway. Her latest books are The Collector of Lives: Giorgio Vasari and the Invention of Art, cowritten with Noah Charney, and The Divine Spark of Syracuse (December 2019). Photographs: Louis Vignes/J. Paul Getty Trust.

For an account of the current situation in Palmyra, see Hugh Eakin’s piece “Ancient Syrian Site: A Different Story of Destruction,” in the current issue of the New York Review.