The talks that opened this week between the North and South Korean governments are off to an inauspicious start: Even before negotiators could settle into their seats, the North had pocketed its first concession from the South, offering nothing in return.

North Korean negotiators are practiced hands in the art of “we win and you lose” deal-making. Unless the team of President Moon Jae-in of South Korea has the fortitude to stand up to such ploys and has a solid game plan of its own, there is a serious risk that the South, its allies and much of the international community will come out of these apparent peace overtures even less secure than before.

The upcoming North-South dialogue was decreed by Kim Jong-un in his New Year’s Day address, after two years of brushing off diplomatic feelers from Seoul. Mr. Kim declared that now — as in, right now — was the time for the two sides to meet to “improve the relations between themselves and take decisive measures for achieving a breakthrough for independent reunification without being obsessed by bygone days.” Seoul rushed to accommodate Mr. Kim’s timetable.

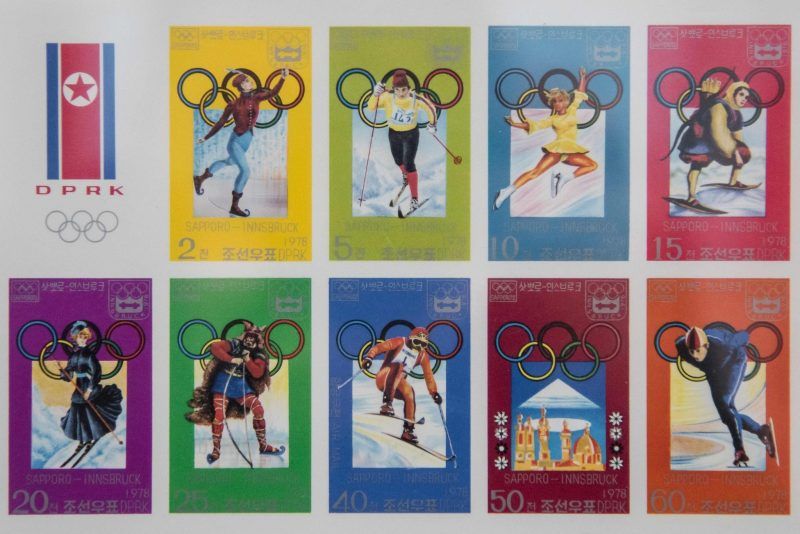

The North’s sudden move ostensibly is explained by its desire to participate in the Winter Olympics next month, which will be hosted in South Korea. But those games were awarded back in 2011, and Mr. Kim’s New Year’s speech is an important annual ritual, prepared and polished months in advance.

By springing this surprise right before the start of the event, the North imposed a hurried and artificial deadline for results. This is “we say jump, you ask how high” diplomacy in action — which is effective for showing who is in control of the negotiation process. Sometimes it also pushes adversaries into making unforced errors.

The South Korean government, in its haste to make ready for dialogue with the North, almost immediately wrong-footed itself. It pre-emptively proposed delaying the joint annual United States-South Korean winter military exercises until after the Games. (Washington acquiesced after high-level consultations.) Seoul may have intended this gesture in the spirit of good will or magnanimity, but it sent all the wrong signals — including a willingness that may be read as weakness, and could harden Pyongyang’s posture, raising its expectations for what it might be able to take back home. The South Korean government, in other words, is off to a bad start, at least tactically.

As far as strategy goes, it is absolutely critical for Seoul — but also for the international community — to understand what may be the calculations underlying Mr. Kim’s move. In particular: Why did he propose talks with only South Korea? And why now?

The simplest interpretation may be that Pyongyang regards South Korea as the weakest link in the gathering global campaign to pressure North Korea to denuclearize.

Moon Jae-in, South Korea’s new and immensely popular president, is a progressive from a camp that favors so-called sunshine policies, and fervently aspires to reconciliation with North Korea through détente, economic engagement and increasing interdependence. But those policies have a checkered track record.

In 2000, their first major proponent, the former president and Nobel Peace laureate Kim Dae-jung, secretly and illegally paid Kim Jong-il, North Korea’s leader at the time, hundreds of millions of dollars to secure a summit. Roh Moo-hyun, the next South Korean president, later strained relations with the United States by trying to take on a balancing role between Washington and Pyongyang — playing arbiter, in other words, between the ally committed to Seoul’s military protection and the regime committed to Seoul’s destruction.

To his credit, in his short time in office Mr. Moon — who, by the way, was one of Mr. Roh’s top advisers during those troubled years — has leavened his own sunshine yearnings with a strong dose of realpolitik. He has pushed for missile defense, for example, as well as for close coordination over international sanctions with the United States despite new strains with President Trump. Last week, Mr. Moon is reported to have said of the upcoming talks with North Korea, “I will not just naïvely push for dialogue as in the past.”

Still, Pyongyang seems to have kept in reserve the option of going on a charm offensive with him. It has already dismissed President Trump as a “dotard.” It called Barack Obama a “wicked black monkey.” It cursed Park Geun-hye, the previous president of South Korea, as an “old, insane bitch.” But it has had nothing bad to say about Mr. Moon (yet).

Meanwhile, the urgency of the North’s diplomatic drive can be explained by both recent wins and menacing losses ahead. Over the past several years, Pyongyang has tested atomic bombs — and, it claims, one hydrogen device — and has launched intercontinental missiles. According to Mr. Kim, the United States mainland is now “within range of our nuclear strike” and his defense sector is moving to “mass produce” nuclear warheads and ballistic missiles.

All the same, the North’s military rests on an economic base that is not only tiny, but also notoriously dysfunctional and desperately dependent on foreign resources and so uniquely vulnerable to serious sanctions. The United Nations Security Council has voted for new and potentially crippling penalties. China — North Korea’s main financial backer — appears finally ready to reconsider, and reduce, its support.

To date, at least by outward appearance, the North Korean economy has not been much fazed by international sanctions. But we do not know how fast the North is spending down its reserves. Only Mr. Kim does.

If Mr. Kim is indeed in a race against the clock to forestall economic disaster at home, importuning Seoul to help lift (or at least ignore) international sanctions, relax nuclear counter-proliferation efforts and revive sunshine economic programs could be the most expeditious way to get out of a bind.

So how can the Moon administration avoid getting played? First, by recognizing the North’s ulterior goals in these talks, and the other traps it may be readying. Then, by insisting ruthlessly on a quid pro quo at every step — requiring, for example, that if Seoul postpones military exercises, then Pyongyang should too. And finally, by tucking a few tricks up its own sleeves.

Mr. Kim says he wants more contact between the North and the South? Insist on it, including by requiring that news from South Korea be allowed to reach the North. Don’t shy away from raising unpleasant topics, like North Korea’s appalling human rights situation, and calling for it to cooperate with the existing United Nations commission of inquiry. And why not confidentially mention that a large majority of South Koreans now seem to favor hosting United States tactical nuclear weapons to counter the North’s new threats?

South Korean negotiators are not used to turning the tables on their North Korean interlocutors, but they should start.

Nicholas Eberstadt is a political economist at the American Enterprise Institute.