In 2006, when I first considered performing in a hard-core pornographic video, I also thought about what sort of career doors would close once I’d had sex in front of a camera. Being a schoolteacher came to mind, but that was fine, since I didn’t want the responsibility of shaping young minds.

And yet thanks to this country’s nonfunctional sex education system and the ubiquitous access to porn by anyone with an internet connection, I have that responsibility anyway. Sometimes it keeps me awake at night — but I try to do what I can.

Pornography was not intended as a sex education program. It was not intended to dictate sexual practices, or to be a how-to guide. While some pornographers, like Nina Hartley and Jessica Drake, do create explicitly educational content, pornography is largely an entertainment medium for adults.

But we’re in a moment when the industry is once again under scrutiny. Pornography, we’re told, is warping the way young people, especially young men, think about sex, in ways that can be dangerous. (The Florida Legislature even implied last month that I and my kind are more worrisome than AR-15s when it voted to declare pornography a public health hazard, even as it declined to consider a ban on sales of assault weapons.)

I’m invested in the creation and spread of good pornography, even though I can’t say for certain what that looks like yet. We still don’t have a solid definition of what pornography is, much less a consensus on what makes it good or ethical. Nor does putting limits on the ways sexuality and sexual interactions are presented seem like a Pandora’s box we want to open: What right do we have to dictate the way adult performers have sex with one another, or what is good and normal, aside from requiring that it be consensual?

I’m invested in the creation and spread of good pornography, even though I can’t say for certain what that looks like yet. We still don’t have a solid definition of what pornography is, much less a consensus on what makes it good or ethical. Nor does putting limits on the ways sexuality and sexual interactions are presented seem like a Pandora’s box we want to open: What right do we have to dictate the way adult performers have sex with one another, or what is good and normal, aside from requiring that it be consensual?

Still, some pornographers have been taking steps to try to minimize porn’s potential harm to young people and adults for years. And one way we’ve been trying to do so is by putting our work into its proper context.

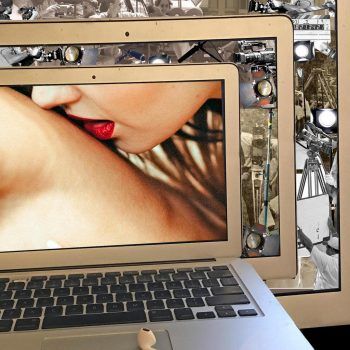

Context reminds people of all the things they don’t see in the final product. It underscores that pornography is a performance, that just as in ballet or professional wrestling, we are putting on a show. For years the B.D.S.M.-focused website Kink provided context for its sex scenes through a project called Behind Kink, with videos that showed the scenes being planned and performers stating their limits. Their films also showed a practice called “aftercare,” in which participants in an intense B.D.S.M. experience discuss what they’ve just done and how they’re feeling about it. (Unfortunately, the Behind Kink project lost momentum and appears to have stalled out in 2016.)

Shine Louise Houston, whose production company is dedicated to queer pornography, has live-streamed behind the scenes from the set, enabling viewers to see what making pornography is really like. I have always tried to provide at least minimum context for my explicit work, through blog posts and in promotional copy.

Many other performers and directors maintain blogs or write articles discussing scenes they particularly enjoyed doing or sets they liked being on, and generally allowing the curious to get a peek behind the metaphorical curtain. Some, like Tyler Knight, Asa Akira, Christy Canyon, Annie Sprinkle and Danny Wylde, have written memoirs.

When viewers have access to context, they can see us discussing our boundaries, talking about getting screened for sexually transmittable infections and chatting about how we choose partners. Occasionally, they can even see us laying bare how we navigate the murky intersection of capitalism, publicity and sexuality.

But this context is usually stripped out when a work is pirated and uploaded to one of the many “free tube” sites that offer material without charge. These sites are where the bulk of pornography is being viewed online, and by definition don’t require a credit card — making it easier for minors to see porn. And so the problems that come with porn are inseparable from the way it’s distributed.

How it’s distributed also shapes the type of porn that is most readily available to teenagers. I frequently hear pornography maligned as catering only to men. That’s not quite fair: Most heterosexual pornography caters to one type of man, yes, but to ignore the rest does a disservice the pornographers who have been creating work with a female gaze, or for the female gaze, for decades.

Candida Royalle founded Femme Productions in 1984 and Femme Distribution in 1986. Ovidie and Erika Lust have been making pornography aimed at women for over 10 years. Of course, their work also isn’t the sort of content that’s easy to find on free sites. But plenty of men enjoy this sort of work, too — just as some women like seeing bleach blondes on their knees.

Sex and sexual fantasies are complicated. So much of emotionally safer sex is dependent on knowing and paying attention to your partner. We in the industry can add context to our work, but I don’t know that it’s possible, at the end of the day, for what is meant to be an entertainment medium to regularly demonstrate concepts as intangible as these. We cannot rely on pornography to teach empathy, the ability to read body language, or how to discuss sexual boundaries — especially when we’re talking about young people who have never had sex. Porn will never be a replacement for sex education.

But porn is also not going anywhere. That means that we have a choice to make. We can hide our heads in the sand, or we can — in addition to pushing for real lessons on sex for young people again — tackle the job of understanding the range of what porn is, evaluating what’s working and what we can qualitatively judge as good, and try to build a better industry and cultural understanding of sex. I choose to try.

Stoya is a pornographer and freelance writer.