Anyone looking to understand how same-sex marriage went from legal in one state to the law of the land a decade later should not overlook the small crowd that gathered outside San Diego’s Manchester Grand Hyatt hotel just past noon one Friday in July 2008, holding signs that said, “The Hyatt of hypocrisy.”

Those present had been rallied by a retired Republican political operative named Fred Karger. His aim was the defeat of Proposition 8, a ballot measure that if passed, would ban same-sex marriage in California. Instead of aiming to mobilize voters or move public opinion against the measure, however, he decided to target the money behind it.

Doug Manchester’s $125,000 donation was not the biggest to the pro-Proposition 8 cause, but he was the most substantial public-facing target Mr. Karger could find. He began picketing Mr. Manchester’s pre-eminent holdings, including the namesake downtown convention hotel, with a boycott that would endure for years. It was the first time gay-marriage activists adopted a strategy of scaring their most well-heeled opponents away from the fight.

Long before the phrase “cancel culture” entered the lexicon or Republican senators complained about the power of “woke capital,” Mr. Karger refined a digital-era playbook for successfully redirecting scrutiny to the opposition's financial backers. The movement to legalize same-sex marriage is often understood as one of civil rights test cases. And indeed, savvy legislative lobbying, fortuitous demographic change and pop-culture influence all played their part, too. But a largely forgotten story is the way a group of political entrepreneurs changed the economic terrain on which cultural conflict was waged. They demonstrated that shaming and shunning could amount to more than an online pile-on and serve as a potent tactic for political change.

The impact on the marriage debate became visible in November 2012, when same-sex-marriage advocates won four states after losing in every one of the 35 that previously put the question before voters. A mix of targeted boycotts and general cultural disapprobation combined to create such a stigma around disapproval of same-sex marriage that many of the opposition’s largest individual, corporate and institutional backers effectively ceded the conflict to their rivals.

Since the first statewide ballot measures relating to marriage, in 1998, the two sides had competed roughly at parity. In 2004, when 13 states approved constitutional amendments against same-sex marriage, $6.8 million went to support their passage and $6.6 million against, according to an analysis by the National Institute for Money in Politics. In 2008, when three more states adopted constitutional bans, $49.8 million was spent in favor and $50.8 million against.

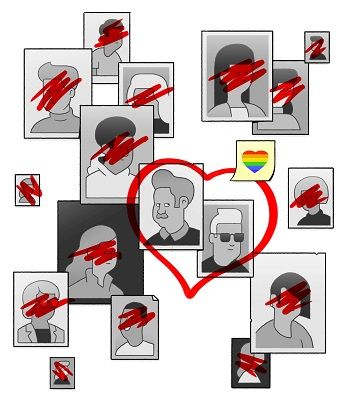

It was that year Mr. Karger decided to make famous every significant donor to the $40.5 million effort to pass Proposition 8. His group, Californians Against Hate, mined disclosure reports and listed everyone who contributed $5,000 or more to pro-Prop 8 committees on a “dishonor roll” website, with phone numbers and business addresses. Other activists made the data searchable via Google Maps, and he pitched out-of-state newspapers to cover local megadonors to the pro-Prop 8 group Protect Marriage.

He picketed upscale supermarkets in New York City and Washington, D.C., to discourage shoppers from buying smoothies and dressings from Bolthouse Farms, whose eponymous founder put $100,000 behind the referendum. After Proposition 8 passed, Mr. Karger led a two-week boycott of the Utah-based Ken Garff Automotive Group, which had 53 dealerships across three states, because one of Mr. Garff’s relatives had given $100,000 to pass Proposition 8. “Individuals and businesses gave a vast amount of money to take away our equality, and we want you to know who they are,” Mr. Karger wrote.

Previously, the boycott was far more frequently a tool of gay rights opponents than supporters. While the American Family Association promoted boycotts of Disney and American Airlines for gay-friendly policies, gay rights organizations went in a different direction. The Human Rights Campaign preferred the carrot to the stick, brandishing its leverage over the private sector by offering to promote model companies in its corporate equality index.

But Mr. Karger recognized how the internet had lowered barriers to rallying consumers. Instead of relying on national organizations to mediate their activism, individuals could start and promote their own boycotts. While news organizations covered his protest at the Grand Hyatt, he was not dependent on them to get out information; he disseminated information about his targets on a blog.

They treated Mr. Karger’s boycott not as a stratagem but as a breach of decorum. Many instinctively responded (much like those who today cry “cancel culture”) by celebrating their victimhood. Mr. Manchester said it was a “free-speech, First Amendment issue.” Brian Brown — the executive director for California of the National Organization for Marriage, the leading single-issue anti-gay-marriage group, led by people with close ties to leaders in the Catholic Church and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints — boasted after the Grand Hyatt protest that Mr. Karger’s “bullying” had backfired. The “stunt they pulled against Doug Manchester ended up raising $100,000 for the amendment in 24 hours,” Mr. Brown said in a message to supporters, “and prompted at least 2,000 new marriage supporters to join our ranks.”

But Mr. Manchester did not remain sanguine for long. The next year, he dispatched an aide to an International Gay and Lesbian Travel Association conference with an offer: $25,000 in cash and $100,000 in hotel credits for dropping the boycott. No one appeared to accept the deal, and Mr. Karger kept up the pressure on the hotels, persuading business groups to yank conferences. In late 2010, Mr. Manchester was forced to sell the property.

Others on the receiving end of Mr. Karger’s boycotts attempted to push back. Protect Marriage challenged California’s campaign-finance system in federal court, arguing that disclosure rules threatened First Amendment freedoms with a “systematic attempt to intimidate, threaten and harass donors to the Proposition 8 campaign.” In 2009, the National Organization for Marriage sued Maine, arguing that laws requiring the release of donors’ names were unconstitutional. (Courts upheld both states’ campaign-finance regimes.)

At the same time, the U.S. Supreme Court opened up channels for corporations to spend freely on campaigns, and Mr. Karger was a model for other online rabble-rousers. In the summer of 2010, lefty activists pushed Target to repudiate its $150,000 donation to MN Forward, an independent group formed to marshal corporate funds for Republican gubernatorial candidate Tom Emmer. MoveOn collected 150,000 signatures on an anti-Target petition, and 44,000 people expressed support for a Facebook page calling for a nationwide boycott because Mr. Emmer supported a constitutional amendment to define marriage as between one man and one woman. That threat led Target’s chief executive, Gregg Steinhafel, to deliver an unusual message to employees saying he was “extremely sorry” for having approved the donation.

By the time marriage came to four states’ ballots in November 2012, it was clear activists had succeeded in making it “socially unacceptable to give vast amounts of money to take away the rights of a minority,” as Mr. Karger put it. Only five individuals, none of them well known nationally, contributed over $100,000 to any of the anti-gay-marriage campaigns in 2012.

Even religious denominations responded to the new pressure. In Maine, the Catholic Diocese of Portland, which had donated $550,000 to pass Question 1, a 2009 ballot measure banning same-sex marriage, did not directly contribute anything when the issue came up again in 2012. Alan Ashton — a WordPerfect co-founder who served as a Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints bishop and stake president and was a grandson of a former church president — donated $1 million to Yes on 8. Four years later, he, too, seemed to have walked away from the issue.

“The impact of donors being scared off was significant,” said the National Organization for Marriage’s chief strategist, Frank Schubert. “The first thing they wanted to know is, ‘Am I going to be publicly disclosed?’”

On the other side, however, new donors emerged beyond the tight circle of gay philanthropists who funded marriage-equality advocacy in past election cycles. Overall, more than two-thirds of the money spent on ballot referendums in 2012 went to advance same-sex marriage. Only in Minnesota was there anything approaching parity between the sides. In Washington State, where Amazon’s founder, Jeff Bezos, and his wife gave $2.5 million to a campaign to pass Referendum 74, which would legalize same-sex marriage in the state, proponents outspent opponents more than five to one.

While pro-gay-marriage activists usually credited changes in their persuasive messaging to their improved campaigns, their most obvious new advantage came in the form of resources. There was only one week in 2012 when anti-gay-marriage ads outnumbered pro-gay-marriage ads in the states with November ballot measures, and in the largest major media markets, pro-gay-marriage campaigners averaged a two-to-one advertising advantage.

Since then, calls for boycotts — as part of a broader ideological cause rather than a narrow protest against specific business practices — have grown so frequent that American politics often feels like a proxy war between corporations. When Equality Matters unearthed donations to anti-gay causes from the family that owns Chick-fil-A, some gay activists proposed boycotts, while Republican politicians elevated eating the chain’s sandwiches into something of a principle. Something similar happened when conservatives called for a boycott of Nike after it released an ad featuring the quarterback and civil rights activist Colin Kaepernick. The Grab Your Wallet campaign disseminated a Google spreadsheet of companies with ties to Trump family members, leading retailers like Nordstrom to drop Ivanka Trump’s product line. After the Parkland, Fla., shooting, gun control activists sought to undermine the National Rifle Association by aiming at large publicly traded companies like Delta and FedEx that offered specific discounts for the association’s members.

In the absence of any political accountability for politicians who indirectly encouraged the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol, recriminations have been felt in the marketplace. Businesses made a dramatic show of withholding contributions from elected officials who voted not to recognize the presidential election results, and have spoken out about electoral measures they consider anti-democratic. Activists and media figures offended by these corporate moves have responded by threatening boycotts. Those who revel in being targeted may come to realize the benefits they reap are short term while the long-term impact is far more than just symbolic.

Sasha Issenberg is the author of The Engagement: America’s Quarter-Century Struggle Over Same-Sex Marriage.