On Sunday, Ecuadorians head to the polls to elect legislators as well as a replacement for the thrice-elected President Rafael Correa, the longest-serving chief executive in the country’s history. Along with policy changes, the country may see some shifts in the proportion of female legislators.

Here’s what you need to know about Ecuador’s presidential and legislative elections, where voting is mandatory:

1) There are 8 presidential candidates

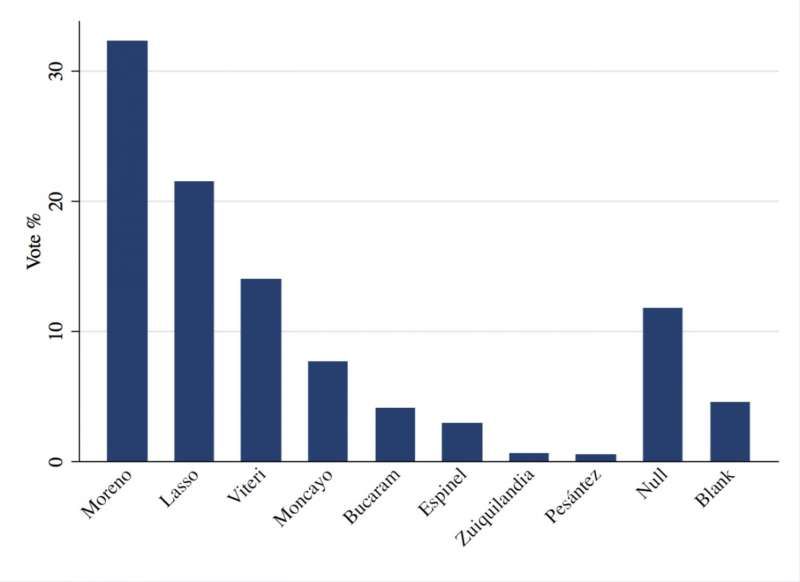

The last official survey results, released Feb. 8 before a government-imposed media blackout, showed a tight race. Front-runners are the ruling Alianza PAIS (AP) candidate, Lenín Moreno, who served as vice president from 2007 to 2013; and the Creando Oportunidades (CREO) movement’s Guillermo Lasso, a conservative former economy minister and banker who was a distant presidential runner-up in 2013.

The Feb. 8 survey of decided and undecided voters gave Moreno 32 percent of likely votes versus 21 percent for Lasso, and 14 percent for former congresswoman Cynthia Viteri. The center-left ex-mayor of Quito, Paco Moncayo, has just 8 percent support, and the four other candidates representing minor parties are polling at 4 percent or less for each. Nearly 12 percent of respondents would cast a null vote to reject the field.

However, a whopping 35 percent of these voters are undecided, meaning more than a third of Ecuadorians are not wedded to a single candidate, adding a high degree of uncertainty to Sunday’s proceedings.

2) This is what Ecuador’s electoral system looks like

Ecuador uses a two-round voting system for its presidential election. To win outright and avoid a runoff election, presidential candidates need to get 40 percent of the vote and hold at least a 10 percent advantage over the nearest rival in the first round. The poll numbers suggest no candidate will win outright, however.

It seems likely that Moreno will end up in an April 2 runoff with Lasso or Viteri. Given political polarization in the country, the opposition hopes that anti-government sentiment will push voters to coalesce around a single candidate.

Ecuadorians will also cast National Assembly votes this Sunday, using the rare free list electoral system, which is somewhat like an extreme version of open lists. Some countries elect their parliaments or congresses using an open list, which lets voters choose among candidates on the list. Others use a closed electoral list, where voters vote for the party itself, rather than individual candidates.

Ecuador’s system, however, allows voters to choose individuals not only within party lists, but among different parties as well. In other words, voters may choose an entire slate of candidates from their party — as in a closed-list system — or cast individual nominal votes among the candidates.

3) How have rules and voter behavior boosted representation by women?

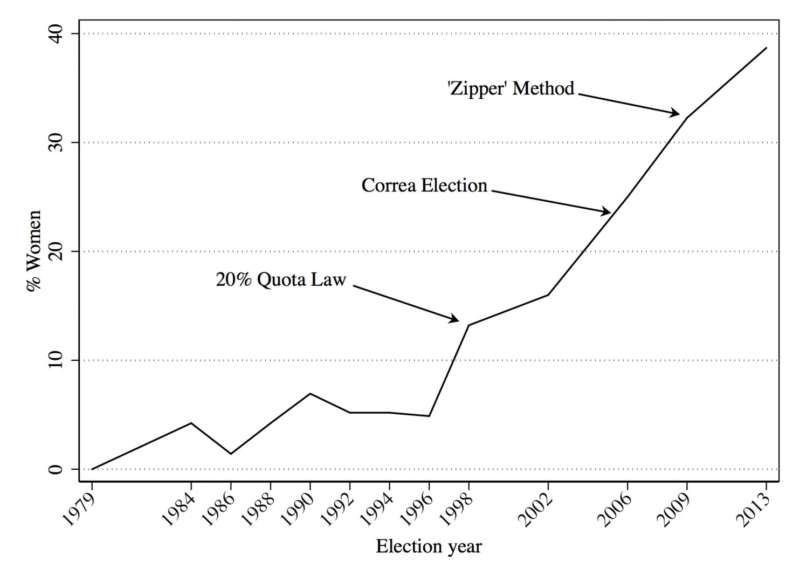

In 2015, Ecuador boasted the third-highest percentage of female legislators in Latin America (53 of 137 assembly members, or 39 percent of its unicameral legislature), behind only Bolivia (53 percent) and Nicaragua (40 percent). Just 25 years earlier, women failed to exceed even 7 percent of Ecuador’s legislature.

Many of these great strides reflect Ecuador’s legislative efforts on gender representation. In 1997, lawmakers introduced a 20 percent quota on party lists, which would increase by 5 percent for each election cycle until parity was achieved.

This law was replaced by Articles 99(1) and 160 of the 2009 Electoral Law, which establish a 50 percent quota — parity — and the alternation of male and female candidates on proportional representation candidate lists, known as the “zipper method”. This means if a party won four seats in a district, for instance, it would be represented in Congress by two male and two female legislators.

4) How might the unusual voting system affect women’s representation in 2017?

In a working project, Tom Mustillo of Purdue University and I found that, buoyed by Correa’s strong presidential coattails and high public approval, AP voters tend to use the party-list option under the free list. But opposition voters tend to cast individual votes across party lines.

The effects on women’s representation are noticeable. Of the 53 female legislators elected in 2013, 46 were Alianza PAIS candidates, and only 7 came from other parties. In fact, as Figure 1 shows, 46 percent of AP legislators were women, compared with just 19 percent of opposition legislators.

AP voters may be more enlightened with regard to gender than are voters at large. But it’s likely that the way voters use the free-list system affects the effectiveness of laws enacted to create gender quotas. Without Correa at the helm of AP, will voters shy away from party lists? If so, the percentage of female legislators will most certainly fall in 2017.

5) What is Ecuador’s ‘muerte cruzada,’ and how might this affect stability?

Correa boasted a majority government for a large chunk of his presidency, the first president to do so since Ecuador’s return to democracy in 1979. Dogged by corruption allegations surrounding the government, AP isn’t likely to earn a majority in the next National Assembly. With their weak organization and national penetration, the opposition parties are even less likely to do so.

This matters a great deal to Ecuador’s political stability. Under a weaker government, the muerte cruzada (“mutual death”) provision in Article 148 of the 2008 constitution gives the president the option to dissolve the National Assembly — and simultaneously cut short his own term. The government would then call for new legislative and presidential elections, with the incumbent allowed to govern by decree on urgent economic matters in the interim.

Muerte cruzada was never a legitimate threat in the latter years of Correa’s presidency. However, this constitutional feature dramatically increases the risks that a divided or minority government might end in deadlock and dissolution.

This could lead to frequent elections and changes of government, as in the decade from 1996 to 2006, when no elected Ecuadorian president served out a full term. It could also increase the temptation for presidents to dissolve parliament so that they can govern unilaterally during the undefined interim period before new elections can be held.

Rafael Correa has dominated Ecuador’s politics since 2007 through good politicking, populist policymaking and closing channels of dissent, as well as a political context he helped shape with a new constitution. While Ecuador has made great strides in women’s representation and enjoyed a decade of political stability, Sunday’s election may mark a step backward. One way or another, though, things are about to change.

John Polga-Hecimovich is assistant professor of political science at the U.S. Naval Academy. The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not represent the views of or endorsement by the Naval Academy, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense or the U.S. government.