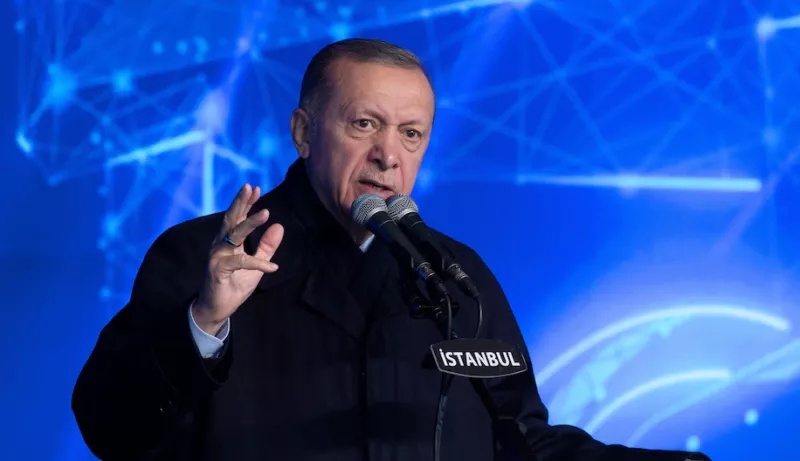

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan knows a thing or two about winning elections — for example, that the best way to secure a victory is to win before the election date.

On Dec. 14, a Turkish court sentenced Erdogan’s most formidable opponent, Istanbul Mayor Ekrem Imamoglu, to two years and seven months in prison. The court (part of a judiciary system largely controlled by the president) also subjected Imamoglu to a political ban. The younger and energetic mayor clearly poses a real threat to Erdogan, whose popularity is sagging as the country prepares for 2023 elections. The president’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) is showing a significant decline in support in polls, and Turkey’s economy is facing hyperinflation that can be managed only by cash flows from friendly powers such as Russia or the Gulf Arab states.

Erdogan has always been a zero-sum politician, willing to resort to almost any means to neutralize his rivals. Yet his attempt to eliminate Imamoglu from the running comes with unprecedented risks — and it could easily backfire if the opposition plays its cards smartly.

The race in Turkey is not over by any means. The Imamoglu decision doesn’t go into effect until it is approved by an appeals court. The opposition camp — six parties that have created a united bloc — would be well-advised to respond to the president’s move by rallying behind the mayor or even considering designating Imamoglu as its candidate.

Technically, of course, the court decision was the product of Turkey’s supposedly independent judiciary, though no one doubts that it came from above. The case itself is Kafkaesque even by Turkish standards. Imamoglu is accused of insulting the judiciary when he described the authorities’ highly suspect maneuverings after the 2019 local elections as an act of “foolishness”.

If a higher court should decide to uphold the ban on Imamoglu in the next few months, the public is likely to react with anger. The opposition’s gambit would pay off. Turkish voters have traditionally punished attempts to overtly meddle with elections. That could make the Dec. 14 decision a blessing in disguise for the opposition if it shows a willingness to take bold steps.

Of course, Erdogan has other moves up his sleeve, and the Imamoglu ban is only one of a series of steps to shape the political playing field ahead of elections. After 20 years in power, and having made many enemies, Erdogan has a lot to lose. Eliminating your key rival is just a start. Turkey’s recently adopted “disinformation bill”, which, critics say, has the potential to restrict free speech and the flow of information on social media, is another risky move.

Erdogan is also playing a skillful hand in geopolitics in ways that he hopes will secure his hold on power in Turkey. He has profited economically and geopolitically from the war in Ukraine by keeping Turkey almost neutral between the West and Russia, in what he calls a “balanced” policy. Turkey is selling drones to Ukraine and helped secure the deal on Ukrainian grain exports. But it has tripled its trade with Russia, and capital inflows from unknown sources to Central Bank coffers — in the vicinity of $28 billion — have prevented an expected balance-of-payments crisis. That, in turn, has enabled the government to disburse new handouts to the public.

The Turkish president is also hoping that he can persuade Vladimir Putin to greenlight another Turkish incursion into Syria right before the upcoming elections — in the hope that this would demoralize or peel off Kurdish voters from the opposition camp by creating a hyper-nationalized atmosphere. Putin may well be open to that.

Yet even though Erdogan remains a master tactician, there are signs he has lost the people’s touch. He is giving his foremost rival an opportunity to follow his own path to political power. Back in 1998, when he was mayor of Istanbul, Erdogan ran afoul of the government, which removed him from power and served four months in jail. Turkish voters never forgave that infringement on their will and brought him back as the winner of the general elections in 2002. He is now giving Imamoglu the opportunity to follow a similar trajectory.

Last week’s decision reeks of anxiety and could become a fatal error of judgment for the Turkish government — if the opposition can manage to make the right moves. Whether Erdogan wins or loses in 2023 likely depends on how bold his rivals are. The majority of Turks clearly want change. This election is for Erdogan to win — and the opposition to lose.

Asli Aydintasbas is a former journalist from Turkey and a visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington D.C.