In 2017, France was lauded for sending an important message to the world: that there was no place for a far-right head of state. At age 39, Emmanuel Macron became the youngest president in French history, defeating far-right candidate Marine Le Pen with 66 percent of the vote. He appeared as the champion of the “Revolution”, which was also the title of his book announcing his ambitious program.

Claiming to belong to neither the left nor the right, Macron and his En Marche party shook up the political landscape. He scooped up so many voters that the socialist party went from being the presidential party in 2012 to ending up with only 6 percent of the vote in 2017.

Macron might have created the illusion of being a newcomer during his 2017 campaign, but many of us remembered he was part of the previous government, which triggered major protests due to an unfair labor law reform that removed regulations protecting workers. Interviewed a few days after his election, I remarked: “Macron is trying to dismantle social laws, the labor laws. He will face many protests on the streets”.

As I expected, Macron has since tended to govern on the right. His current prime minister and most of his cabinet are from the right. The progressives who supported Macron had many expectations of his presidency, but he has not met them.

Soon after he was elected, he suspended the wealth tax, allowing the rich to get richer. He later proposed a pension reform plan that would have gutted France’s welfare system. Huge crowds rallied across France to oppose it, with protests beginning in December 2019 and lasting weeks. Eventually, the pandemic forced Macron to change his plans.

On climate, Macron tried to position himself as a champion of environmental justice, vowing in 2017, when the United States announced its intent to withdraw from the Paris climate agreement, to “make our planet great again”. Four years later, a French court had to order the state to honor its climate commitments.

Macron also received backlash from the public for his appointment of Gérald Darmanin as interior minister. Darmanin has been twice accused of sexual misconduct and abusing power (he has denied the allegations), yet Macron shrugged aside the public protests, initially saying that he had a “relationship of trust, man-to-man” with his minister. A court case was reopened over one of the allegations in 2020, but now appears likely to be dismissed.

On immigration, a controversial bill supported by Macron’s party that tightened asylum rules was described by academic Patrick Weil as a “regression” and the first time “since the Second World War” that a “ruling majority [in France] has dared to go this far”. The party’s stance generated admiration from President Donald Trump, who praised Macron’s leadership on what he termed “uncontrolled migration”.

And finally, after the death of George Floyd, France experienced a significant movement in support of Black Lives Matter. But Macron maintained that France should continue to avoid seriously addressing race, saying he did not “recognize himself in a struggle that reduces everyone to their identity”.

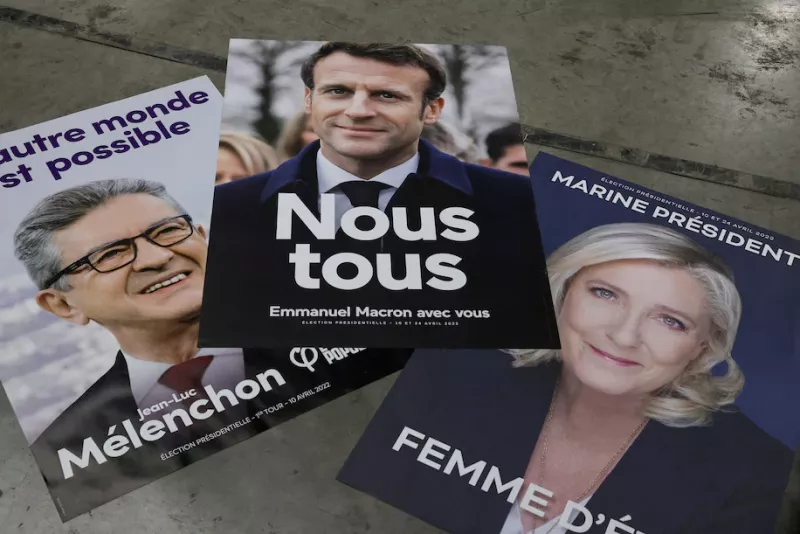

Now, almost five years since his election, France is more divided than ever. The far right has grown in an alarming way. For the first time, it is represented by two candidates — Marine Le Pen and Éric Zemmour — who cumulatively are predicted to receive more than 30 percent of the vote.

Even candidate Valérie Pécresse of the traditional center-right party Les Républicains, initially considered a moderate, has invoked terms and ideas inspired by far-right racist rhetoric. In a recent speech, she explicitly referred to the “Great Replacement” theory that has inspired white supremacists on both sides of the Atlantic and suggests that Islam and migrants are supposedly subverting the purity of the “European” identity.

The strength of the far right in the French political landscape is particularly jarring after the defeats of Trump in the United States and Andrej Babis in the Czech Republic, and given upcoming elections in Hungary and Brazil in which Viktor Orban and Jair Bolsonaro might be pushed toward the exit.

On the left, the socialist party has been unable to recover from its historic defeat in 2017. This accelerated the reconstitution of the left around La France Insoumise, a party that ended up receiving 19 percent of the vote in the first round of the 2017 election and whose vocal candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon is the most likely to challenge Macron on social justice.

As France faces grave international challenges, including the Russian invasion of Ukraine, we need to stand strong and united. With Germany choosing a leader from the left to succeed longtime chancellor Angela Merkel and Chile electing a left-wing president, there is now a chance for France to make similar strides on the road to progressiveness.

Ultimately, this election is an opportunity to choose the progressive way over the discourse of hate and division.

Rokhaya Diallo is a French journalist, writer and filmmaker.