In 1946, just months before independence, carnage unimaginable in ferocity and unprecedented in scale broke out against Hindus in Muslim-dominated East Bengal and against Muslims in Hindu-majority Bihar. The great campaigner for freedom from Britain’s imperial yoke, Mohandas Gandhi, spent weeks in both theaters of what he described as “almost a civil war.” He was determined to quell sectarian violence with his own life if need be.

Gandhi never accepted the “Two Nations” theory, which saw a sanctuary for the subcontinent’s Muslims in a future Pakistan and a natural home for its Hindus in a Hindu rashtra, a Hindu nation. On Aug. 15, 1947, as India won its freedom and the new nation celebrated its new dawn, Gandhi did not join the celebrations in New Delhi. He was in Calcutta, where sectarian riots had disfigured life, even as bloody carnage had left hundreds of Hindus dead in East Bengal and Muslims, likewise, in Bihar.

Freedom had come with the partition of the country on the basis of religion. Gandhi described the day as meant for celebration but also for sorrow.

Calcutta broke into bloody riots within days of independence. Gandhi fasted against the violence. “Kill me, kill me, I say,” he told a Hindu mob. The men who ransacked his dwelling almost killed him but his courage and lack of fear stayed their hand. Hindu and Muslim rioters cowered before Gandhi’s moral force. “I will not leave you in peace,” he told the violent, the hate-filled, the crafty.

He then went to Delhi, the new nation’s capital, which was also seething with the rage of Hindu refugees fleeing from a Pakistan that had no time or place for them. On Jan. 30, 1948, a man who believed Gandhi had betrayed Hindus did to Gandhi what he had always been prepared for. As the leader fell to three bullets fired at point blank range, all hope for religious concord in India, seemed to vanish.

But has it vanished?

Indians, like people anywhere, do not want to hate. They do not want to hug suspicions, fears. But there are those, very political, ambitious and selfish people — men, mostly — who want to use incipient suspicion and fear to control their fellow citizens, turn India into a Hindu rashtra. And bigots on the other side, extremists using the name of Islam, feed Hindu communalism with just what extremists need to stay in business: the violent “other.”

And they love to foment fear. Some fears are real as, for instance, the fear of terrorism, of armed attacks from across borders, of externally orchestrated insurrection. But many other fears are fiction, such as the fear of a Muslim population explosion, a Muslim jihad. And Pakistan’s unpredictable militaristic politics, ever keeping an already conflicted Kashmir in ferment, helps the fire burn.

Two ways of life face India today. A path that wants Indians to have freedom of conscience, thought and speech so that the best ideas and energies can be devoted to raising up the poor, the marginalized and the discriminated and making India a republic for all its citizens. And the road that wants India to be dominated by one political and religious order, one majoritarian grip on all, making India a nation of stark uniformity, a Hindu rashtra.

Who are the Indians seeking a Hindu nation? They are the followers of the Hindu part of the Two Nations theory. Hate, they say, the one who wears clothes different from yours. Mistrust the one who eats foods different from yours, speaks and writes differently, sings songs that are not yours and — most crucially, who prays to a god not yours. If he does all that and even questions some of your beliefs, he is antinational, so just tell him to get out. So it goes, the new majoritarian rhetoric.

Democracy is about majority rule, not majoritarian tyranny. What is under attack in India is not just Hindu-Muslim concord, but the right of all minorities — ethnic, linguistic, regional, political, social and cultural — to be themselves, to be equal, to be free. Dissent, free speech and the freedom to choose with confidence and without fear are under strain.

On Gandhi’s 75th birthday in 1944, Albert Einstein wrote in a book of felicitations, “Generations to come will scarce believe that such a one as this ever in flesh and blood walked upon this earth.” When Einstein said “will scarce believe,” he had in mind Gandhi’s distinctive capacity for nonviolent resistance.

Einstein knew of Gandhi’s having been pitched out of a train in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, because of the color of his skin. He knew that Gandhi led the subsequent resistance by Indians in South Africa against discriminatory treatment, and he knew of his nonviolent ability to suffer persecution and humiliation without physical retaliation.

Gandhi bore no hatred for his oppressors, did not speak or write a harsh word about them but, with his large and growing band of associates, offered the toughest resistance through what he called satyagraha, or soul force. The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela found this capacity in Gandhi compelling, exemplary and even sublime.

Gandhi’s satyagraha was famously illustrated in the Salt March in 1930, when he walked 240 miles with his followers to the village of Dandi on the Arabian Sea in western India. The British had banned the villagers from making salt through seawater reclamation unless they paid a tax. Gandhi, who described it as a “battle of right against might,” lifted a fistful of salt and auctioned it, repudiating the tax and challenging the empire.

At the saltworks nearby, colonial police attacked Gandhi’s nonviolent followers. An American reporter, Webb Miller, who witnessed them being struck with murderous blows from lathis, or police batons, wrote, “So far as I could observe the volunteers implicitly obeyed Gandhi’s creed of nonviolence. In no case did I see a volunteer even raise an arm to deflect the blows from lathis.” Gandhi’s march and breaking the prohibition on salt shook the Raj.

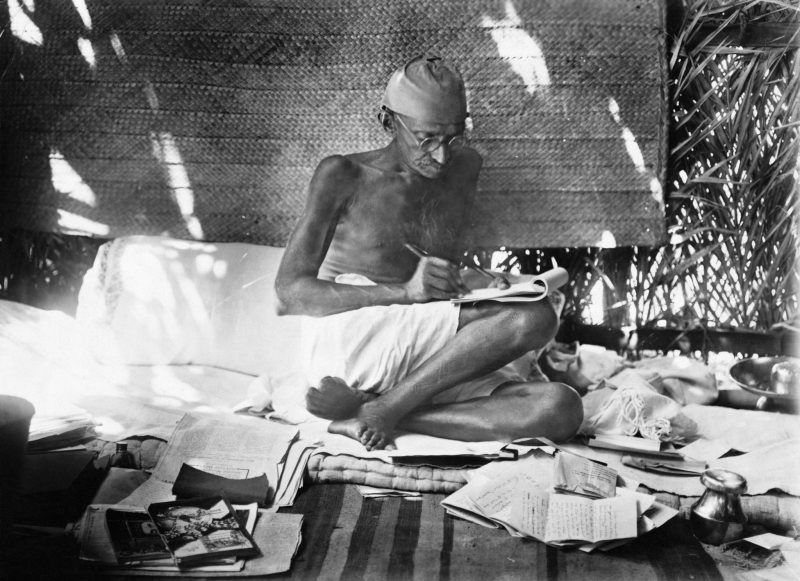

Was Gandhi a perfect man or leader? Certainly not. “Ask Mrs. Gandhi,” he would say. He was his own most exacting critic and wrote frank admissions of his flaws and failures.

The Gandhi of a hundred battles, scarred but not fallen, is facing his greatest challenge in India today. The challenge of neglect, of obfuscation, of cunning co-option. Marigolds are still heaped on his images, the more plentifully by those who hate his truth-telling spirit. Gandhi refuses to be smothered. I will not leave you, he seems to say once more. To another generation of enemies of peace and destroyers of social trust, Gandhi speaks yet again, the voice of right against might. And is again, unbelievable.

Gopalkrishna Gandhi teaches a course on Indian Civilization at Ashoka University in Sonipat, India.