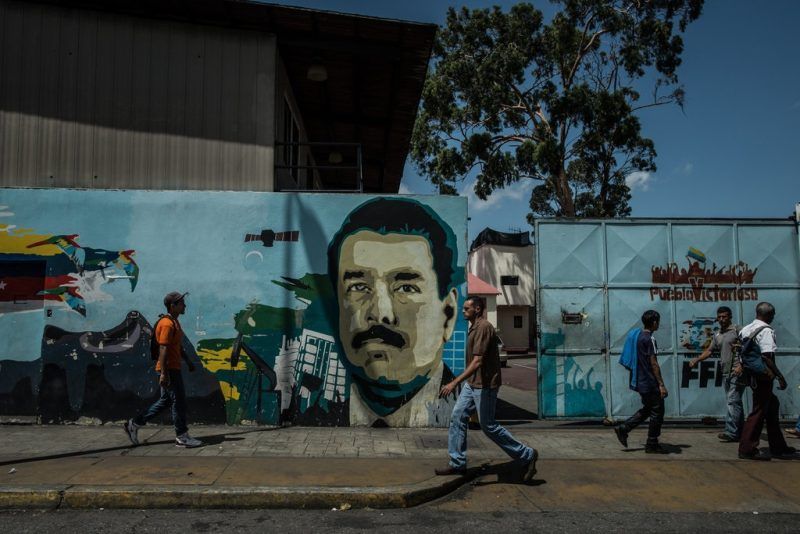

Political arrests are a rare growth industry in Venezuela. When Nicolás Maduro became president after Hugo Chávez’s death from cancer in 2013, there were about a dozen prisoners of conscience, according to Foro Penal, a local nongovernmental organization. Today, the number hovers at around 100, and some 2,000 people are the subject of politically driven judicial prosecutions.

The government’s latest targets are Francisco Márquez and Gabriel San Miguel, two civil servants working in a mayor’s office who were summarily arrested at a highway checkpoint in a remote area of northern Venezuela on June 19. Along with hundreds of other activists, they were traveling that day to help collect signatures to petition for a referendum to remove Mr. Maduro from office.

The recall process, as this kind of referendum is known, is explicitly protected by Venezuela’s Constitution. The secretary general’s office of the Organization of American States, the archbishop of Caracas, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have all denounced the arrest of Mr. Márquez and Mr. San Miguel as politically driven and violations of both international and Venezuelan law.

Once in custody, the two men were kept incommunicado and interrogated without counsel by the feared Cuban-trained secret police forces. They were charged with “inciting violence” and money laundering, crimes that can carry jail terms of more than 15 years. Instead of being kept in a special pre-trial holding facility, they were sent to one of the country’s notoriously dangerous penitentiaries, among convicted criminals.

The Venezuelan government’s decision-making is famously opaque, and there’s no saying for sure if the timing of these arrests was deliberate or coincidental. But coming in the midst of important political negotiations, the episode seems fortuitous for the Maduro government, which has refined the art of using and leveraging political prisoners to its advantage.

Bilateral talks aimed at thawing relations between Venezuela and the United States kicked off in June. José Luis Zapatero, the former president of Spain, is acting as mediator between the Venezuelan government and the political opposition in talks sponsored by Unasur, a grouping of South American countries. And now the Maduro camp has a couple of special political prisoners to deploy as diplomatic pawns: Mr. Márquez has American and Venezuelan citizenship; Mr. San Miguel is a national of both Venezuela and Spain.

The late Mr. Chávez was known for blackballing or persecuting individuals who opposed him publicly. But under his tenure, hard time was largely reserved for insiders deemed to have betrayed the revolution — like Francisco Usón, a general who criticized Mr. Chávez on television, or María Afiuni, a judge who acquitted a Chávez enemy of charges that he had evaded currency controls.

In Mr. Maduro’s more heavy-handed and more paranoid understanding of the Socialist revolution, political arrests are no longer just a mechanism for party discipline. They have become a tactical tool for controlling the national conversation. Acting through pliant prosecutors, judges and the secret police, the Maduro administration has used arrests to feed conspiratorial narratives about plots to overthrow the president, sow discord among opposition factions and, more recently, as bargaining chips.

In 2014, after riots and large-scale political protests broke out over soaring crime, inflation and food shortages, the opposition leader Leopoldo López was arrested and tried for inciting violence. He had been at the forefront of an effort to channel widespread socio-economic frustration into an organized nonviolent resistance movement. But early last year, Mr. López was offered up in exchange for Oscar López Rivera, a leftwing Puerto Rican nationalist who was convicted by a U.S. court in 1981 of masterminding more than 100 bombings against civilian targets in major American cities.

The U.S. government demurred. But there have been successful quid pro quos. In June 2015, following a round of talks between U.S. Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs Thomas A. Shannon Jr. and senior Venezuelan officials, two Venezuelan student protesters were released from jail. In exchange, a high-ranking Maduro administration official under investigation by the U.S. Justice Department for drug trafficking secured a photo–op with Mr. Shannon, and the U.S. State Department is said to have convinced leaders of the Venezuelan opposition to halt a hunger strike.

This time around, with both Mr. Márquez and Mr. San Miguel being dual nationals, the Venezuelan government has even better cards in hand. It could play those to try to obtain, say, the lifting of some U.S. sanctions or the release of two relatives of the Venezuelan first lady currently detained in the United States on drug trafficking charges. Invoking complex diplomatic negotiations could also allow the Maduro administration to stall on the recall referendum.

The U.S. State Department has released a statement saying, “We expect the government of Venezuela to accord any U.S. citizen the full extent of his rights to due process under international and Venezuelan law.” But Venezuela doesn’t recognize dual citizenship for people older than 25. And it hardly has a reputation for fairness: It ranked last of 102 countries in the World Justice Project’s 2015 Rule of Law Index.

Nor is its standing likely to improve. When it barters political prisoners for its own gain, the Venezuelan government is, in effect, turning them into hostages.

Daniel Lansberg-Rodriguez is a political columnist for the Venezuelan newspaper El Nacional and an adjunct lecturer at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management.