By Day Three, I begin to embrace the rhythm: Rise as soon as sunlight streams in through the window I cannot open, await the 8 a.m. doorbell, pause for a moment to give the man on the other side time to move sufficiently far away, retrieve the box of food left outside, retreat, eat. Twice more in the day, we will repeat this dance. The rest of the time, I will be alone, confined to the 230-square-foot hotel room the Singapore government has ordered me not to leave for two weeks.

I do not have the coronavirus — not as far as I can tell. But I am part of the government’s new initiative to combat a recent uptick in coronavirus cases, which was announced the day before I boarded the last Singapore Airlines flight from New York to Singapore for some time on March 25.

The new measures came after Singapore had earned much praise in the global media for its early successes in stemming the spread of the virus. In late January, Singapore moved to ban Chinese visitors and foreigners who had recently traveled to China from entering the country. It mobilized teams of contact tracers who grilled coronavirus patients for hours to connect the social dots of how the contagion may have spread. And so in the early weeks of March, this island city-state of under 6 million people had just 166 reported cases, with 93 patients having been treated and discharged.

No country can truly be an island, however, and that number soon crept up again, fueled in part by droves of Singaporeans and permanent residents escaping the coronavirus onslaught elsewhere. On March 24 alone, the country reported 49 new covid-19 cases, 32 of which were imported, bringing the total to 558. That’s when Singapore mandated that all travelers arriving from the United States and Britain would have to undergo a mandatory two-week “Stay-Home Notice” period served in lodgings chosen and paid for by the government. (On Friday, in the face of still-rising numbers, the Singapore government announced it would close most workplaces and schools, shifting to home-based learning, while also restricting social gatherings and encouraging Singaporeans to remain at home as much as possible.)

My decision to return to Singapore was not an easy one. Even as a child, I had bristled at the country’s strict and multitudinous laws that address everything from flushing the toilet to “flying a kite in a way that obstructs traffic.” In 1993, I left for college in the United States, determined to carve out a new life in which free speech and civil liberties were paramount. Over the years, I had come to think of those freedoms as basic, natural and necessary.

And here I was now voluntarily stepping into an indefinite future in which I’d be subjected to an ever-growing list of laws and initiatives designed to fight the virus. Citizens, for example, recently have been encouraged to download a new contact tracing app that uses wireless Bluetooth technology to constantly identify and log the phones and people near you. The idea is that this would help identify people who have been within two meters of coronavirus patients for at least 30 minutes.

The Stay-Home Notices, or “SHNs” as we call them, come with many rules. (Of course.) The three-page “information sheet” that greeted us in our rooms began with a cheerful “Welcome home!” before launching into a list of tough penalties.

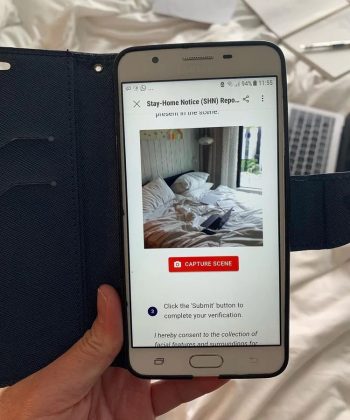

Twice a day, I get a text message requiring me to verify my whereabouts. On occasion, I have had to take a photograph of myself, as well as my surroundings, to prove I am where I am supposed to be. My phone’s GPS has to be on so I can be tracked. The hotel delivered a thermometer to me on my first day here so I could take my temperature twice a day and report immediately if a fever was detected.

In addition to the texts, I get a daily phone call from the hotel checking to see how I’m feeling. On Day Four, when the upbeat voice on the other end asked if I was finding the food improved, I found myself wondering how much our social media was being monitored, having just bemoaned the quality of our meals on Instagram. And indeed, the revised information sheet delivered the night before included a paragraph advising us “to not speculate and/or spread falsehoods and rumors” on social media.

To be sure, we are not enduring any true hardships here. There have even been unexpected moments of levity — a growing band of us inmates have been finding one another on Instagram, like secret revolutionaries reaching out to others in captive kinship. We marvel at one another’s room photos and bitterly circulate pictures of beautiful meals we are unable to eat. At one resort, a flautist and a violinist in quarantine have been giving impromptu concerts on their balconies. In these penned-in times, I’ve learned the weight of such minutiae.

When I’ve shared tidbits of my days so far in this government quarantine, many American friends have been shocked that hundreds of people would so unquestioningly submit to being confined and monitored in such a fashion.

My own response to this has astonished even me. I have found myself vociferously defending and explaining my country’s draconian quarantine strategy. So perhaps it’s true that you can take the girl out of Singapore, but you can never take Singapore out of the girl. The foundation of my native country was built with an emphasis on placing family above self, society above family, country above society and so forth. I may have rebelled against this before, but in these times, I am increasingly convinced that even a dollop of this ethos is going to be what ends up saving us all.

Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan is a New York-based journalist and author of Sarong Party Girls and A Tiger in the Kitchen: A Memoir of Food and Family. She is the editor of the fiction anthology Singapore Noir.