In 1983 the Irish people voted to give a fertilized egg the same right to life as the woman who carries it. Feminists tried to stop it. We argued that crisis pregnancies were a reality of women’s lives and that we needed the right to choose how to deal with them. We said that the constitutional amendment on the ballot, which made abortion illegal unless the mother’s life is in danger, would harm women. We marched and chanted “Get your rosaries off our ovaries”. A Catholic bishop pronounced that the most dangerous place for a baby was in a woman’s womb.

We lost, overwhelmingly. But Ireland has changed. On May 25, the Irish people will vote on whether to repeal the Eighth Amendment. This time I think we can win.

Contraception had not long been legalized in Ireland in 1983. There was no divorce. The Roman Catholic Church was enormously powerful. I was working at a rape crisis center in Belfast, in Nothern Ireland, and six of us packed into a Mini and crossed the border into the republic to take part in the campaign against the amendment. In Donegal, the most northern county in the Republic, we handed out a poster featuring a drawing by the artist Käthe Kollwitz, of a mother pulled every which way by her needy children. “It’s life that needs amending, not the constitution”, it said. A boy hissed at us that we should be raped and made pregnant. Our posters were flung to the ground.

In Carndonagh, a small town in Donegal with a steep main street dominated by a large Catholic church, two nuns took down our poster and told us to go back to where we came from. Donegal had one of the highest majorities for the amendment in the country.

Soon after the vote, a 15-year-old girl gave birth and died along with her baby boy in a grotto for the Blessed Virgin in a rural town. No one admitted knowing she was pregnant. In 1992 the authorities tried to stop a suicidal 14-year-old girl who was pregnant as a result of rape from traveling to England for an abortion. After that, the amendment was changed to allow “right to travel” and to obtain information. In 2012, a dentist named Savita Halappanavar was refused an abortion in a Galway hospital during a miscarriage that lasted three days. She died of septicemia. There were other harrowing stories.

Now some 3,000 women leave Ireland each year for abortions, while an unknown number go online to order pills that induce a miscarriage.

In a n April poll, 47 percent of those surveyed said they would vote for the repeal, while 28 percent said they would vote against it. The rest are undecided. If the referendum passes, the government is expected to make abortion on request legal until the 12th week of pregnancy.

Of course, there are still passionate abortion opponents in Ireland. I went to a “Save the Eighth” meeting in the County of Sligo. Speakers compared abortion to the Holocaust, death camps in Cambodia and wars in the Middle East. It was claimed that in Britain, the bodies of babies are burned to heat hospitals.

And the church is still trying to influence the debate. A priest, the Rev. Francis Bradley, recently told a newspaper in Inishowen that 20 years ago Irish people had “voted to take violence and death off our streets” through the Good Friday Agreement. If we repealed the Eighth Amendment we would reverse this and be guilty once again of “victimizing the innocent”, he said.

But the church does not have the moral authority it did in ’83. There have been revelations of child abuse and cruelty toward pregnant women — scandals the church did its best to cover up. At the same time, the women’s movement has grown, and women have begun to speak out about their experiences of crisis pregnancy and abortion. And the return of Irish emigrants from more liberal countries has driven change: Divorce is now legal, as is same-sex marriage.

So I went back to Donegal, where repeal campaigners had set up information stalls on the main streets of Carndonagh and other towns. People willingly stopped to discuss their views. That would have been unimaginable in 1983.

‘Sometimes a woman just needs an abortion’

Cathy Shiels was not yet born when the Eighth Amendment was voted into the Irish Constitution. Now 23, she lives in Dublin and has been a feminist campaigner for years.

After talking to the women in her family, Ms. Shiels believes that Carndonagh, where she was born, has changed. “My Granny said after Savita Halappanavar died that it was wrong, and that the woman had to come first”, she said.

‘My generation is not so indoctrinated’

“People have become more pragmatic — they are more supportive of young women who have babies when they aren’t married and they keep them in the family. In the past that was a big disgrace. But people also see that sometimes a woman just needs an abortion”. She thinks the referendum will pass, but she is not complacent. “Every vote is going to count”, she said.

“Women should be allowed to choose. It’s their body. It doesn’t belong to the Church”, Katherine McBride, who is 13, told me. “I didn’t understand religion at school and I didn’t accept it. My generation is not so indoctrinated as earlier ones. We aren’t afraid of the thought police. We talk about these things in school. We debate them in class. Most of my friends are pro-choice, though some are on the fence”.

Katherine has been going to pro-choice meetings with her mother, Bernie Linnane, for a couple of years. Bernie is proud of her daughter. She was a teenager when the Eighth Amendment was added to the Constitution. “The people who are leading the campaign to save the Eighth Amendment have been rejected by the electorate many times in recent years”, she says. “They have lost on divorce, gay marriage, contraception and sex education. Once the Catholic church loses on this campaign it has lost everything”.

‘You don’t necessarily have to be pro-abortion to be pro-choice’

Nora Newell worked as a family-planning nurse in London before she returned to Ireland in the period leading up to the 1983 amendment. “At that time less than a quarter of doctors in Donegal were even providing contraception”, she said. “The church and its teachings saturated everything. You couldn’t penetrate it”.

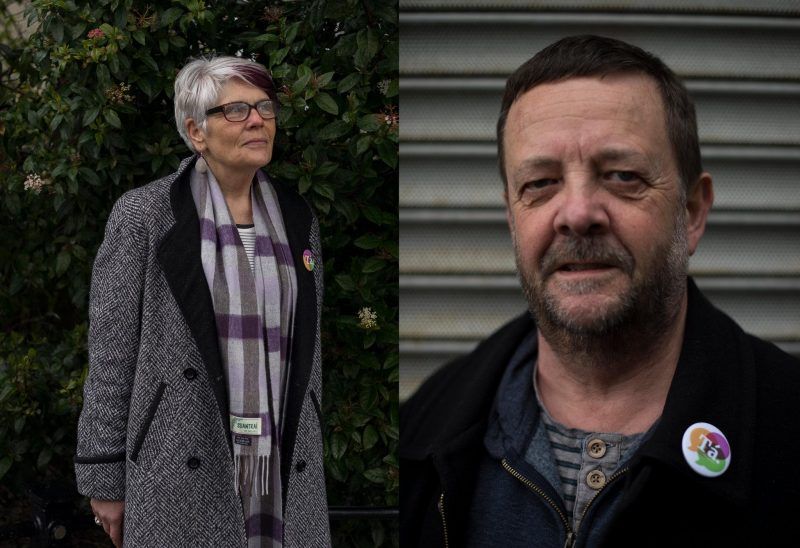

Now she is married to Tim Spalding and both are deeply involved in the “Repeal the 8th” campaign in Donegal.

“This time we are focusing on personal stories about how real people are affected”, Mr. Spalding said. “We are willing to listen. We are saying that you don’t necessarily have to be pro-abortion to be pro-choice”.

‘When I was 19 I got pregnant unexpectedly’

Sinead Stewart is a 42-year-old mother of two. “I grew up in a pro-life home”, she said. “Mum was in the Legion of Mary and very, very Catholic. When I was 19 I got pregnant unexpectedly — I decided to go on with the pregnancy and that’s when I became aware of how difficult it all was”. Sinead said she was treated “abominably” in the hospital because she was an unmarried teenager. “As a young girl you just take it — you don’t even realize you shouldn’t be treated like that”.

She attended an anti-abortion meeting in Donegal recently and said she was shocked by the extreme language used by some of the speakers. “It was like a Bible Belt of America way of doing things, frightening people”, she said.

‘We have to keep the momentum going’

Cathal O’Sullivan, 29, from Buncrana, now lives in Derry. Mr. O’Sullivan was active in the Marriage Equality movement in 2015.

“After we won, my local bar here was all done up with rainbow flags to celebrate. I remember a woman jumped up on a table and shouted, ‘the next campaign is for a woman’s right to choose!’ We have to keep the momentum going”.

In Buncrana, Mr. O’Sullivan manned a stall handing out leaflets. Most people took one, though some refused. “No thanks. I’m pro-life”, one young woman said. “So are we”, Mr. O’Sullivan replied.

•

I’ll never forget that road trip in 1983, those nuns who banished us from Carndonagh. We lost, and women paid a heavy price. But we’ve dispelled so much shame now. There is a new confidence in Irish feminism. Today it is possible to say, “This is what we need to live our lives”.

Susan McKay is writing a book about the Irish border.