After President Michelle Bachelet of Chile leaves office in March, Latin America will have no female presidents.

There was a time in 2014 when the region had four: Laura Chinchilla in Costa Rica, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner in Argentina, Dilma Rousseff in Brazil and Ms. Bachelet. Now, Latin America is left with few prospects for female presidents in the near future.

More than most regions, Latin America has used affirmative-action laws to close the gender gap in political leadership. But to hold these gains, and to help ensure that women continue to rise to top political positions, Latin America needs to understand the limits of legal remedies for pulling women up.

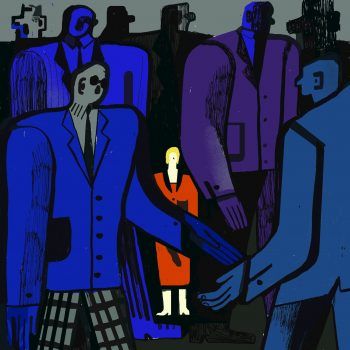

Quota laws for female legislative candidates have created opportunities for women to advance in politics, but they have not fully transformed traditional attitudes about who should lead a country.

Women entered national congresses in significant numbers thanks to gender quotas. Argentina passed the world’s first quota law for female candidates for Congress in 1991, requiring political parties to nominate women for at least 30 percent of the open positions. It was recently updated so that half of parties’ congressional slates must be women. Today, all but two Latin American countries have a quota or parity law for legislative candidates.

Women hold more than 35 percent of legislative seats in Costa Rica, Ecuador, Mexico and Nicaragua. Bolivia has a majority-female legislature. In the United States, by comparison, women make up just 19 percent of the House of Representatives and 22 percent of the Senate.

Women hold more than 35 percent of legislative seats in Costa Rica, Ecuador, Mexico and Nicaragua. Bolivia has a majority-female legislature. In the United States, by comparison, women make up just 19 percent of the House of Representatives and 22 percent of the Senate.

Many of these quota laws do more than increase the number of female candidates. Many require political parties to place women in favorable ballot positions and to allocate portions of their budget to training female leaders.

But while affirmative-action laws help women get ahead, they do not save them from political crises.

Ms. Bachelet, Mrs. Kirchner, Ms. Rousseff and Ms. Chinchilla led popular incumbent parties when they were elected president, in a region already accustomed to female leaders. The three presidents on the left — Ms. Bachelet, Mrs. Kirchner and Ms. Rousseff — also benefited from the “pink tide,” a wave of leftist leadership that swept Latin America from 1998 to 2016.

In this period, the region was buoyed by a commodities boom. Flush with resources, countries expanded social protections for workers, the poor, indigenous peoples, L.G.B.T. people and women.

Then the party ended: Economies declined and security concerns increased. Citizens became disillusioned, and the traditional parties and their coalitions broke apart. Voters decided to throw most incumbents out, men and women alike.

But the women fell harder than the men, making clear that there is still a double standard for male and female leaders.

Ms. Chinchilla’s presidency was widely seen as a failure, even though the economy grew 4 percent to 5 percent during her term. Ms. Bachelet’s favorability nose-dived following allegations that her son and daughter-in-law profited illicitly from real estate, while President-elect Sebastián Piñera apparently suffered no ill effects from allegations that he faked invoices to illegally finance a campaign.

In 2016, Congress impeached Ms. Rousseff and removed her from her office for accounting practices that were long held as normal in Brazil, and with no evidence of her personal enrichment. Upon taking over from Ms. Rousseff, President Michel Temer chose only white men for his new cabinet, in a country where nonwhites are the majority. Mr. Temer recently faced accusations of corruption more serious than those against Ms. Rousseff, including allegations that he ordered his subordinates to pay hush money. He survived his impeachment vote.

Neither the left nor the right in Latin America appears to want female candidates these days. The left, favored to win after Ms. Chinchilla’s departure in Costa Rica, passed over the longtime political leader Epsy Campbell Barr. A prominent politician of African descent, Ms. Campbell Barr lost her bid for the party’s nomination for president despite having approval ratings higher than those of her male competitors.

And on the right, the Mexican politician and former first lady Margarita Zavala had strong poll numbers but no path to winning the nomination. She recently started an independent campaign for the presidency — in a video criticizing the party for closing ranks against her.

These are not isolated events. My research shows that political parties from the left and right nominate fewer women when voters think the economy is doing poorly. Political parties on both sides also nominate fewer women when there is increased competition. In Latin America, disillusionment has fueled the growth of new parties. More choices for voters means fewer seats for each party — and parties with fewer seats to win appear less likely to take chances on women.

More women in office also does not mean less discrimination or harassment. The glass ceiling remains.

While Latin America outpaces the global average for women in senior management roles, women hold only 5 percent of board seats in six of Latin America’s largest economies. Within legislatures, women rarely lead their parties’ delegations, and they remain absent from the most prestigious committees.

In Colombia, a study found that nearly a quarter of female elected officials felt silenced and were denied resources by their parties, and 40 percent of female mayors reported sexist treatment. Sometimes, resistance to female politicians takes violent forms. Parties have long undermined quotas by asking women to resign once elected: Juana Quispe, a councilwoman in Bolivia, was beaten to death for refusing to do so.

Gender and parity laws matter, and they have too much public support for politicians to roll them back. Even conservative Chile now has a gender quota for the legislature, which almost doubled the number of women in Congress in the election where the right made a huge comeback.

But ending the sexism and hostility that drives women from power requires changing cultural attitudes and ending impunity toward violence against women.

Costa Rica has tackled traditional notions about who should lead by applying quotas to the civil-society sector. By law, nonprofit organizations must have gender parity in their top leadership positions. This includes charitable, humanitarian and social-service organizations, bringing men into positions from which they’ve historically been absent.

After all, if more women take power in politics and business, men will need something else to do.

Jennifer M. Piscopo is an assistant professor of politics at Occidental College.