I grew up with an aversion to India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru.

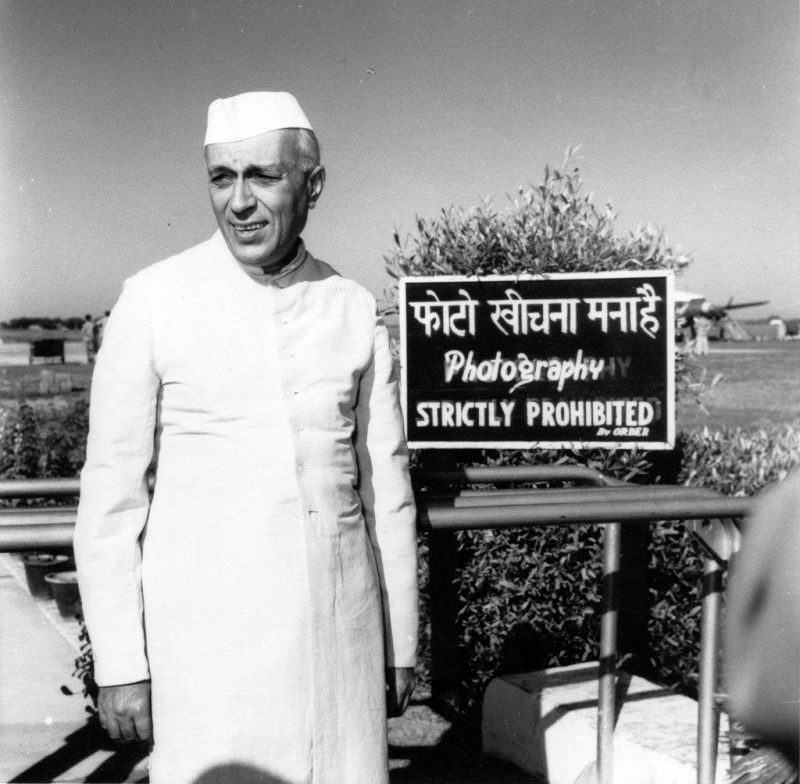

He was the towering figure of the postcolonial world. Harrow and Cambridge-educated, he was one of the architects of the Non-Aligned Movement, which sought a third way through the odious binaries of the Cold War. In India, he dominated the political landscape and is credited with laying the foundation for our country’s democracy.

The cult of Nehru continued through his heirs. His daughter, Indira Gandhi, and grandson, Rajiv Gandhi (no relation to Mahatma Gandhi), both went on to be prime minister. Nehru died in 1964, and by the time I was growing up, some two decades later, the brand of socialism he had championed was failing. The impression that came down to me of this father of Indian democracy was of a fey creature, embarrassingly Anglicized, making grandiloquent speeches in an Oxbridge accent about light and freedom and “trysts with destiny.”

By then, India was changing. The economic reforms of the 1990s had empowered a new class of Indian, less colonized, more culturally intact. We entered an age when authenticity was prized above all else, and Nehru, by his own admission, was not authentic, not culturally whole. He was a hybrid, forged on the line between India and Britain, East and West. The reputation of Mahatma Gandhi, though he was no less a hybrid, survived the change. Nehru’s did not.

Nehru today is a figure of revulsion on the Hindu right, which governs India. The era of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party is in every respect a repudiation of Nehru. Mr. Modi represents authenticity and Indianness; Nehru is the quintessential foreigner in his own land.

Every year, around Nehru’s birthday on Nov. 14, a battle rages in which the bedraggled remains of India’s left try to defend the first prime minister, even as an increasingly louder chorus of voices on the right portray him as having been soft on Muslims and having betrayed the interests of the Hindu majority.

His ease with Western mores and society is a liability, for it implies an apparent contempt for Hindu culture and religion. Nehru comes to seem almost like a symbol of a country looking at itself through foreign eyes, and in a newly assertive India, his legacy is being dismantled. In at least one B.J.P.-controlled state he is being completely written out of textbooks; he is maligned daily on social media, with hashtags like #knowyournehru.

Which brings me to an embarrassing confession: Nehru is one of those people I thought I knew without ever feeling the need to read. He was among the great literary statesmen, and his output was prodigious: letters, speeches, famous books like “The Discovery of India” and “Glimpses of World History.” And there is his autobiography, “Toward Freedom,” in which he truly comes alive.

I have at last been reading Nehru, now at this hour when his stock is at an all-time low. And I have yet another embarrassing confession to make: He’s wonderful. It is not just a question of the peerless prose — the American journalist John Gunther was quite right to say that “hardly a dozen men alive write English as well as Nehru.” Nor is it simply that he is a man of astonishing reading, intellect and sensitivity. What makes Nehru so compelling is his acute self-knowledge. There is practically nothing you can say against him that he is not prepared to say himself.

Consider him on the subject of his own deracination. In “Toward Freedom,” he writes: “I have become a queer mixture of the East and the West, out of place everywhere, at home nowhere. Perhaps my thoughts and approach to life are more akin to what is called Western than Eastern, but India clings to me, as she does to all her children, in innumerable ways.” He continues: “I am a stranger and alien in the West. I cannot be of it. But in my own country also, sometimes I have an exile’s feeling.”

Nehru, unlike Mr. Modi — who is decidedly not a reader and who has an almost childish regard for the Indian past — can look hard at himself and his country. “A country under foreign domination seeks escape from the present in dreams of a vanished age, and finds consolation in visions of past greatness,” he writes in “The Discovery of India.”

Nehru is never more prescient, seeming truly to speak across the decades, than when he addresses the nationalism that will one day endanger his vision of India. “Nationalism,” he writes in “Toward Freedom,” “is essentially an anti-feeling, and it feeds and fattens on hatred against other national groups, and especially against the foreign rulers of a subject country.”

I was stunned, reading these lines at a moment when Mr. Modi’s Hindu Renaissance has proved to be precisely the “anti-feeling” Nehru described: a culture war against two enemies, Westernized Indians and the country’s approximately 170 million Muslims.

If Mr. Modi stands for authenticity, Nehru forces us to question the premium we place on it. He forces us to ask ourselves if purity is even desirable, and whether India’s true genius does not lie in its ability to throw up dazzling hybrids, like Nehru, who seem, in intellect and sophistication, vision and worldliness, to be every bit Mr. Modi’s superior.

Mr. Modi has certainly ushered in an age when the “Indian soul” — like the German and Russian soul before it — is finding utterance. But what is it saying? Last month, in Rajasthan, a state whose government is run by the B.J.P., we were given yet another sampling of what Mr. Modi’s brand of authenticity looks like: a Hindu man axed to death a Muslim man, then set the body alight, while asking his nephew to film the murder.

The killer posted the video on Facebook. He wanted to send a message that the “Love Jihad” — a baseless B.J.P.-promulgated conspiracy theory in which Muslim men lure unsuspecting Hindu women into marriage and conversion — would not be tolerated. The response of the B.J.P. leadership was, as it usually is after such killings, strategic silence.

Rajasthan, in recent months, has become a byword for this kind of religious murder. It also happens to be one of those states where last year Nehru was erased from school textbooks. Otherwise the eighth graders there might have grown up with these words of his, which the historian Ram Guha quoted last month in an essay for The Hindustan Times: “If any person raises his hand to strike down another on the ground of religion,” Nehru said on Gandhi’s birthday in 1952, “I shall fight him till the last breath of my life, both at the head of government and from outside.”

Time may have trifled with Nehru. But time will also reveal him to be the giant that he was.

Aatish Taseer is a contributing opinion writer and the author, most recently, of the novel The Way Things Were.