Is the political disarray in the United States really ŌĆ£a godsend for AmericaŌĆÖs criticsŌĆØ or a ŌĆ£propaganda coupŌĆØ for them? Is Chris Coons, a Democratic senator from Delaware, correct to warn that the crisis of American democracy ŌĆ£feeds into the playbooks of authoritarian leaders around the world?ŌĆØ

Hua Chunying, the spokeswoman of ChinaŌĆÖs Foreign Ministry, for one, has called out some U.S. officials and politicians for describing protesters in Hong Kong as ŌĆ£democracy heroesŌĆØ but saying that the Trump supporters who stormed the U.S. Capitol last week were ŌĆ£thugsŌĆØ and ŌĆ£extremists.ŌĆØ

RussiaŌĆÖs first deputy ambassador to the United Nations, Dmitry Polyanskiy, denounced on Twitter the fact that protesters who entered the Capitol ŌĆ£Maidan-styleŌĆØ ŌĆö referring to the 2014 uprisings in Ukraine, which garnered much support in the West ŌĆö were being described as ŌĆ£criminals.ŌĆØ

The spokeswoman for RussiaŌĆÖs Foreign Ministry, Maria Zakharova, has argued that the event ŌĆ£has once again brought our attention to the archaic electoral system of the United States.ŌĆØ

On Jan. 7, an editorial in Global Times, a nationalist tabloid controlled by the Chinese Communist Party, declared ŌĆ£an internal collapse of the U.S. political system.ŌĆØ On Wednesday, in reaction to Mr. TrumpŌĆÖs impeachment in Washington, it published an editorial titled: ŌĆ£The World is So Different: China is Fighting the Epidemic, the U.S. is Fighting for Power.ŌĆØ

And so? Does the deepening of cracks in AmericaŌĆÖs political system actually boost the legitimacy of China and other authoritarian regimes?

The United StatesŌĆÖ self-portrayal as a beacon of democracy has been contested for many years, well before the Trump presidency ŌĆö with shocking expos├®s about American soldiers torturing Iraqi detainees at Abu Ghraib or the National Security AgencyŌĆÖs unlawful surveillance program. The Trump era has only offered more ammunition to AmericaŌĆÖs critics, including poignant images of immigrant children in cages and George FloydŌĆÖs death at the hands of the police or apocalyptic scenes of American hospitals overcrowded with Covid-19 patients.

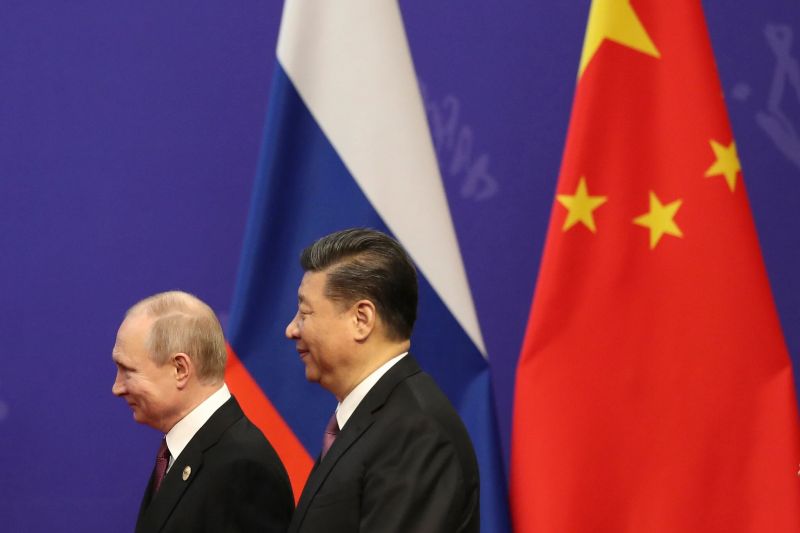

The recent acceleration of the United StatesŌĆÖ apparent self-destruction might have emboldened China and Russia to adopt even more assertive postures on the international stage: at the United Nations and with the World Health Organization; in the South China Sea, Ukraine or Syria. Yet damage to AmericaŌĆÖs reputation doesnŌĆÖt actually bolster the reputation of authoritarian states. There is no direct connection between the two.

Admittedly, I argue this based not on a sustained or systematic analysis of media coverage, debates on social media or public opinion surveys ŌĆö that work takes time ŌĆö but on an early analysis of current coverage and my research about political communication in authoritarian countries, especially China. So far I see no reason to believe that even this hard a hit to AmericaŌĆÖs prestige will burnish the image of authoritarians elsewhere.

ChinaŌĆÖs global stature has suffered since the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, even though the country has fared better than many major states in managing the crisis. In a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center in 14 industrialized countries in the fall, three-quarters or more of respondents in most of those countries saw China ŌĆ£in a negative light,ŌĆØ a much greater proportion than the previous year. A majority of respondents in another Pew study from the summer also held consistently negative views about Russia.

Does the propaganda work at home?

Chinese and Russian media coverage of the current crisis in Washington is designed to fuel nationalistic sentiments in both countries, and to some extent it succeeds at that.

Take this popular post by Global Times showing side-by-side pictures of the storming of the Capitol last week and of the protesters who broke into Hong KongŌĆÖs Legislative Council building in July 2019. Here is a comment responding to it that attracted more than 1,000 likes: ŌĆ£The ŌĆśbeautiful sightŌĆÖ that Pelosi favors has finally happened in her own office,ŌĆØ referring to Nancy Pelosi, the speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, who had used the phrase to describe not the LegCo break-in but a 2019 vigil in Hong Kong for victims of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre. The comment also said, ŌĆ£The United States doesnŌĆÖt have double standards. It simply has no standard for right and wrong.ŌĆØ

At the same time, the chaos in Washington was widely broadcast on both mainstream media and social media in China, and mostly with little censorship, which is unusual. Allowing or even facilitating that flow of information seems to have been a propaganda gambit. But it could backfire for the Chinese government by breeding more fascination with the United States among Chinese viewers, especially if the story in America becomes a tale about the resilience of a democracyŌĆÖs institutions against a dangerous president.

Some of the discussion on Chinese social media has analyzed the recent events in granular detail, drawing historical analogies. Commenting on a video that recorded the sound of a gunshot inside the Capitol, one Weibo user described it as ŌĆ£the Lexington gunshot,ŌĆØ a reference to the beginning of the American Revolution. Another Weibo user compared a picture of Trump supporters waiving a ŌĆ£Make America Great AgainŌĆØ flag on top of a car to ŌĆ£Liberty Leading the People,ŌĆØ the famous painting commemorating the July Revolution of 1830 in France.

And then, of course, thereŌĆÖs the fact that Mr. TrumpŌĆÖs attempted coup failed. That the electionŌĆÖs results have been certified. That he eventually ŌĆö if belatedly and, it seems, reluctantly ŌĆö denounced the violence of some of his supporters. And now, that he has been impeached again.

After Hu Xijin, the editor in chief of Global Times, claimed in a Weibo post on Jan. 7 that AmericaŌĆÖs democratic system had just imploded, one Weibo user argued instead, ŌĆ£the American systemŌĆÖs capacity to rectify mistakes is strong; it has withstood the challenge,ŌĆØ adding: ŌĆ£If this were the Chinese system, Trump could continue to stay as the president. Of course, China should prevent someone like Trump from taking office.ŌĆØ

Again, these comments are only tidbits of evidence, snapshots of one moment taken from broader, dynamic social media discussions; they will need to be studied further, in greater context, with more perspective. But they already suggest that perceptions in China and Russia about the political upheaval in America may wind up being shaped less by Chinese, or Russian, propaganda than by AmericaŌĆÖs response to its crisis.

The storming of the U.S. Capitol and the dramatic political fallout from that isnŌĆÖt a gift for authoritarian leaders bent on denouncing AmericaŌĆÖs shortcomings so much as an opportunity for America to rebuild itself and its image worldwide. It is how America itself handles this crisis in the weeks and months ahead that will determine how this story, and America at large, ultimately is perceived by people in China, Russia and beyond.

Maria Repnikova, a 2020-21 fellow at the Wilson Center, is an assistant professor of global communication at Georgia State University and the author of Media Politics in China: Improvising Power Under Authoritarianism.