As Europe’s fall election seasons wraps up, observers continue worrying about an ongoing threat to democracy from populism. A quarter of Austrian voters cast their ballots for the far-right Freedom Party. In the Czech Republic, voters put an anti-establishment, anti-E.U. billionaire in the prime minister’s seat. In Germany’s fall election, Alternative for Germany, an extremist party with nativist and anti-immigration rhetoric, entered parliament, the first time a far-right party has done so since 1948. And two regions in Italy voted for more autonomy. Political scientists, journalists and economists have all argued that populism is on the rise.

Not everyone agrees. Political scientist Larry Bartels argued here at the Monkey Cage that there’s no “wave” of populism — that populist sentiment has been there all along but is currently finding new expression.

Our new research supports that conclusion, with some additional nuances. The new populism is hardly unprecedented — and its new success at the polls may simply be the result of more crowded party systems.

How serious is the populist trend?

With very few exceptions, most investigations maintain that votes for anti-establishment parties in Western European democracies have more than doubled in the last 55 years. Similarly, studies going beyond Europe and covering a longer period of time also show that the percentage of votes for extreme parties has significantly increased since the Great Recession of 2008, rising even higher than after the Great Depression in 1929. And anti-establishment parties in recent European elections from Bulgaria and the Czech Republic to the Netherlands and France have certainly garnered larger shares of the vote.

But this “populist trend” might not be as widespread as previously assumed. In particular, if we look more closely at the data and pay attention to individual elections, we can see that support for anti-establishment parties greatly differs among countries.

It might not be as common as it looks

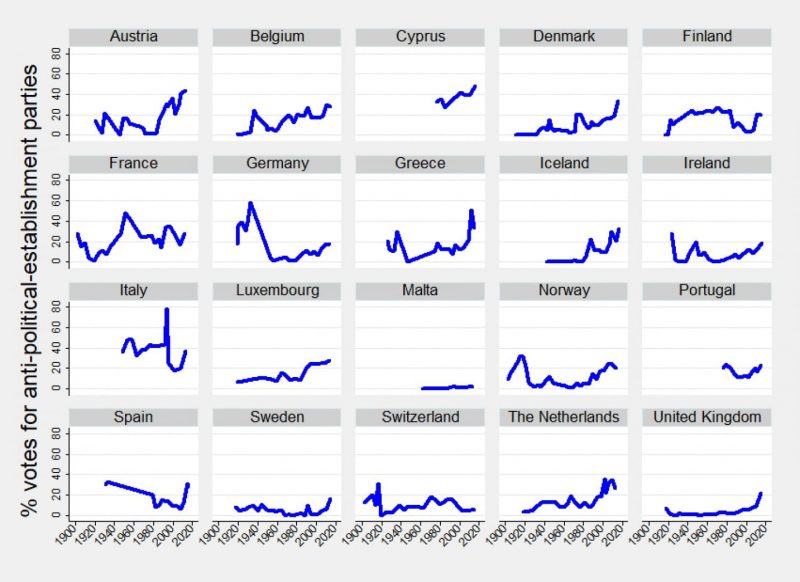

The figure below displays the support for anti-establishment parties in 20 consolidated Western European democracies since the end of the 19th century, using data from 474 elections available at the “Who Governs Europe” project.

If we look at populist parties’ successes over this longer period, we can see four things.

First, with just two exceptions — Switzerland and Malta — the share of votes for anti-establishment parties rose between 2000 and 2010. That increase has been especially notable in the last three years.

Second, in most European countries, that share has been increasing since the end of World War II — except in the trends that you see in Switzerland, Malta, Finland, Italy and, to a lesser extent, Portugal and Great Britain.

Third, conventional wisdom correctly notes that the countries with the most notable spikes in populist votes are also those most affected by the 2008 recession (it is true in the cases of Cyprus, Greece, Iceland, Italy and Spain — countries that were hard hit by the recession — but this relation does not work in the cases of Portugal and Ireland) and by the recent migration crisis (it is true in the cases of Austria, France, the Netherlands and Germany — countries that experimented with notable increments in the percentages of immigrants in the last years). However, most nations that were democracies before the 1970s are seeing a trend of smaller vote share for anti-establishment parties than they did between the world wars, with the exceptions of Austria, Denmark, Greece, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom.

Moreover, in a significant number of countries, the election with the highest percentage of votes for populist parties took place well before 1995, including Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Norway, Portugal, Spain and Switzerland.

In fact, if we were to rank the elections with the highest support for anti-establishment parties in all 20 democracies displayed in the table below, we would observe that most of the elections with a record number of populist votes were in the 1930s, 1990s and 1950s, as well as in the 2010s.

Looking at this historically, we can see that the story isn’t as simple as the current conventional wisdom would have it. There’s no clear pattern from one nation to the next that can be summarized by saying populism is on the rise because of the 2008 economic and financial crisis. Every nation has a different history — and we have look at each case in particular.

More, but smaller, anti-establishment parties than in the past

Further, there’s been another change at the same time — and it may be complicating the picture. Not only have anti-establishment parties been getting a larger share of the vote; European countries have seen a parallel rise in the number of parties in the electorate.

That matters. When just one radical party (like the Communists or fascists) obtains a high percentage of votes — as happened during the 1930s — the nation is facing something quite different from when various political parties get those votes. In the first case, the radical party has a great deal of power to pressure or blackmail the government. That’s just not true when those votes are spread among many parties. Consider France, which has at least four anti-establishment political parties: National Front, France Unbowed, French Communist Party and French Arise. While the National Front has gotten the most attention, its power is less than if those anti-establishment votes gone its way.

So should we really be worrying about populism?

Looking at all this information, we might ask ourselves if the current rise in support for populist parties is such a big deal. With the exception of Greece — the nation most affected by the 2008 recession — no E.U. country has had a “populist” prime minister. Most European governing coalitions — the exceptions are Norway, Finland and Belgium — do not even include a populist party.

As a result, we question the announcement of a new era of democratic doom. Are we currently facing a period of realignment? Certainly. Has the economic crisis revealed democracy’s shortcomings? No doubt. But we do not believe we are currently witnessing the collapse of European party democracy.

Fernando Casal Bértoa is an assistant professor at the University of Nottingham in Great Britain.

José Rama Caamaño is a PhD candidate at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid in Spain.