Pakistan has found a new ally in its never-ending war against India — and he is the public face of our most ruthless killers.

For years Liaquat Ali, better known as Ehsanullah Ehsan, was a familiar and dreaded figure on national media. It seems that after every atrocity committed by the Pakistani Taliban, or Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), he would make triumphant statements in audio messages or bloodcurdling videos, putting the fear of God in Pakistani media and causing revulsion among Pakistani people.

Soon after the TTP killed three employees of Express TV in January 2014, the television channel invited Ehsan on the air by phone. He very calmly explained the reasons for the murder, and the interviewer promised — respectfully, repeatedly — to give him more airtime, while begging for guarantees that there would be no further attacks.

Ehsan later claimed responsibility for an Easter Day attack in a park in Lahore last year, which killed dozens of people. He had previously claimed responsibility for an attack on a girl named Malala, who was shot in the head on her way to school, adding that the TPP would hunt her down if she survived.

Ehsan later claimed responsibility for an Easter Day attack in a park in Lahore last year, which killed dozens of people. He had previously claimed responsibility for an attack on a girl named Malala, who was shot in the head on her way to school, adding that the TPP would hunt her down if she survived.

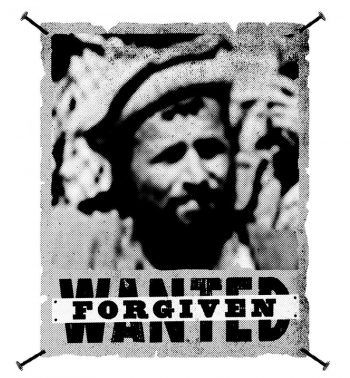

With his appearance, the Pakistani Army seemed to be sending this message: You can kill thousands of Pakistanis, but if you later testify that you hate India as much as we do, everything will be forgiven.

There was some pushback. State media regulators banned a detailed interview with Ehsan before it aired after families of Taliban victims expressed outrage. The parents of students slain at the Army Public School in Peshawar in 2014, where Taliban attackers butchered more than 140 people, mostly students, wanted Ehsan hanged in front of the school.

But the army has preferred to parade him and his winning smile in front of TV cameras, and to release footage of him telling salacious stories about how his Taliban colleagues had three wives or how the current TTP leader took away his teacher’s daughter by force. The purpose seems to be to suggest that the Taliban are not a formidable force with an ideology and deep roots in Pakistani society, but rather a bunch of sexual perverts bankrolled by India. India, forever our existential enemy.

There is, it’s true, evidence that India has funded groups to strike at Pakistan for interfering in Kashmir. But do we really need to enlist our children’s killers in our campaign against India?

Pakistani society is still deeply divided over what the Taliban represent. Some see them as barbarians at our door who want to destroy the last vestiges of our faltering democratic and civil order. Others think of them as our misguided brothers: The Taliban, too, want a just society; it’s only their methods that are unacceptable. They are brave, and we are a little bit proud of them: In Afghanistan, these fallen brothers, our creation, are still managing to keep America at bay.

But when they wage the same brave fight in Pakistan, we recoil.

The Taliban were supposed to be our assets in our historic feud with India. When India and Pakistan were on the verge of another war in 2008, the Taliban leaders of the day vowed to fight alongside Pakistan’s soldiers.

“If they dare to attack Pakistan, then, God willing, we will share happiness and grief with all Pakistanis,” said Maulvi Omar, the Pakistani Taliban’s spokesman then. “We will put the animosity and fighting with the Pakistani army behind us, and the Taliban will defend their frontiers, their boundaries, their country with their weapons.”

Today, while the nation is still trying to decide if yesterday’s monster can be today’s patriot, the Pakistani Army has already made it clear that it wants to have the last word on the subject.

The leading English daily Dawn reported last year that the civilian and military leaderships were divided over what to do with Pakistani anti-India militant groups, which are often accused of waging attacks in India. The army declared that the story was a national security breach, and demanded stern action against both the people who had leaked information about those disagreements and the people who had dared to write about them. A high-powered investigation was set up to look into what has come to be known as the Dawn Leaks.

Last week, after reviewing the results, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif ordered the removal of two of his close aides and referred a journalist to a newspapers’ representative body. The army spokesman tweeted: “Notification is rejected.” The army won’t abide any discussion with civilians over who is a good or bad militant, or a good or bad Pakistani.

Many Pakistanis still love the army. And many politicians fear it. They look to it to remove their rivals, accusing one another of being security threats, if not outright traitors. Many political parties are asking for Mr. Sharif’s head for daring to have a closed-door discussion about what might be wrong with the army’s idea of good and bad.

Most countries have an army, but in Pakistan it’s the army that has a country, goes the saying. If the politicians want to take the country back, they’ll have to stop calling one another traitor just to please the army.

Mohammed Hanif is the author of the novels A Case of Exploding Mangoes and Our Lady of Alice Bhatti, and the librettist for the opera Bhutto.