Next week marks 25 years since the destruction of the Berlin Wall, the physical embodiment of the cold war. President Kennedy had stood by the Wall in 1963 and declared: “Ich bin ein Berliner.” Later, during the era of Glasnost, Ronald Reagan urged the Russian leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, to “tear down this wall”.

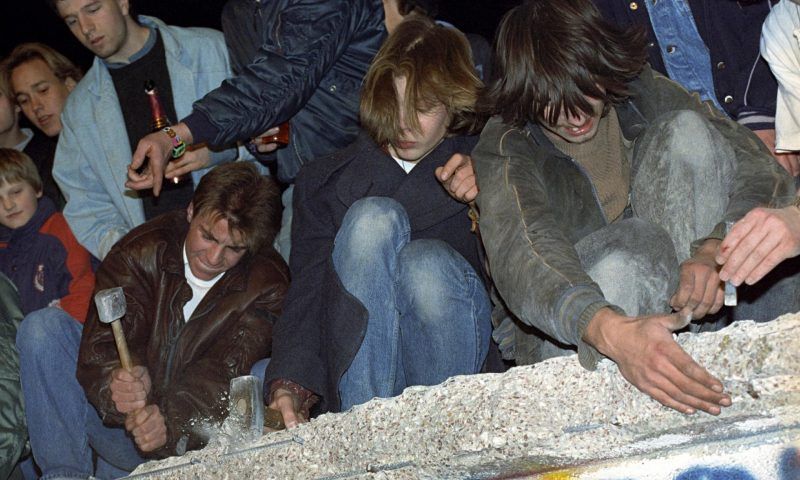

Why did the west want the wall torn down? Because the people living behind it were subject to tyranny and denied their freedom. For anyone of my generation, seeing the wall torn down, not by tanks but by people, is one of the most defining images of our lives. It symbolised the victory of freedom and democracy over dictatorship and tyranny. The fall of the wall was the most important strategic victory for the west in the past 70 years.

With the wall down, how could peace be guaranteed and freedom and democracy be underpinned in the countries of eastern Europe? Admission to the European Union was a critical step. Margaret Thatcher was suspicious of a united Germany but her successor as Conservative leader and prime minister, John Major, championed the admission of the former Warsaw Pact countries to the EU.

Then, as now, EU membership demanded a commitment to democracy and to freedoms that we in the UK cherish. Issues are resolved peacefully, if sometimes messily. The processes may be arcane and frustrating at times but they are never at the barrel of a gun. And war between two member states is now almost inconceivable.

In our current debate over Britain’s relationship with Europe, we are forgetting that the EU’s expansion to the east and the freedoms it conferred was a triumph for the west.

We forget the gains made in terms of peace and democracy, respect for human rights and the freedom of citizens. Instead, we focus relentlessly on what are seen as the costs of our membership, including freedom of movement.

Yet this freedom is a result of a geopolitical change that we in the United Kingdom championed for decades. Other changes, such as the technological revolution, have reinforced the trend, making the global movement of people, capital and ideas much more rapid than before.

All of this means that the world has changed and is much more interconnected today than in the past. The right leadership response to this change is to shape a future within it that gives the most opportunity for all our citizens. Searching for a rewind button is not the answer.

An interconnected world must not be a world without rules, but the rules must focus on the right things. For example, in a world where people move around more, it is right and fair that we have proper conditionality on access to finite public goods such as public housing and benefits. Similarly, it is wrong to have our controls abused by people-trafficking and illegal immigration on the back of trucks in Calais. And when some asylum claims can still remain unresolved after a decade or more, there is clearly a need for reform in the system.

But there is a critical difference between the proper application of rules and trying to go back to a world that has changed irrevocably, in part through our own policy successes.

Twenty-five years after the fall of the wall, turning our backs on the EU and erecting a new kind of wall between Britain and the rest of Europe would be bad for jobs and investment and would ignore the historic victory in which we played such a vital part.

For a Conservative prime minister to lead Britain out of the EU either by design or, perhaps even worse, by default would be a complete failure of leadership.

Our task is to make the most of the much more interconnected world we helped to bring about rather than recoiling from its results.

Pat McFadden is the shadow minister for Europe.