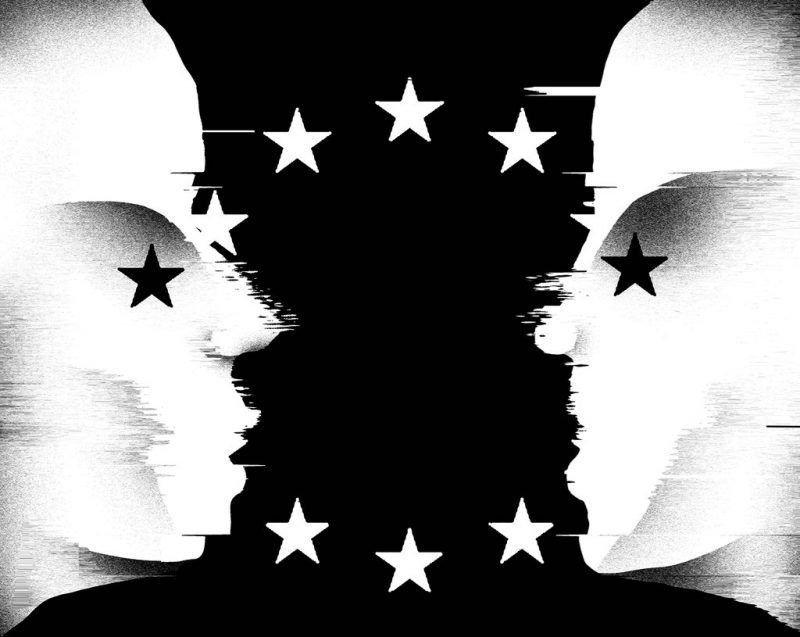

Jihadist attacks, a migrant flood, Greek debt, surging nationalism: Across the European Union, anxiety and division are brewing in a way not seen since the 1940s.

Confronted with this, Europe is paralyzed. And the element most dangerous to the European dream is barely noted: A rift is widening between France and Germany over how to pursue prosperity and security, their deepest national interests.

If France and Germany can’t work together, the dream of a united Europe will shatter. In the 1950s, that premise drove Chancellor Konrad Adenauer and President Charles de Gaulle to a historic understanding: Franco-German cooperation would be the bedrock on which to build Western Europe’s revival. France would lead Europe’s political reconstruction while West Germany powered its economy.

It seemed logical. On the still-smoldering ruins of World War II, the two nations had comparable power, and for 30 years they worked in concert toward a Common Market, a Europe-wide visa policy and plans for a common currency.

But in the 1990s, German reunification undid the balance. French influence waned as Germany’s economy became a juggernaut. The French struggled with globalization, refusing to exchange their social benefits for competitive efficiency. So Germany became the primary voice within the European market.

The common currency arrived, with German banks in the lead. But by 2005, France’s voters had soured on surrendering more sovereignty: In a trendsetting plebiscite, soon followed by one in the Netherlands, they stopped momentum toward an all-Europe constitution. Then came the 2008 financial crash, laying bare the economic gap and political resentments between Northern Europe, driven by Germany, and the less industrious South.

Even more dangerous politically, but less discussed, the crash exposed a growing gap between French and German attitudes toward each other — their labor forces, welfare policies and diplomacy. Last year, terrorism and the Middle East refugee crisis brought that, too, into focus.

Now when they meet, President François Hollande and Chancellor Angela Merkel speak of solidarity, but in different terms. Mr. Hollande declares France “at war with the Islamic State,” while German leaders talk of “fighting terrorism.” The French take on military operations in Mali, Iraq and Syria, while Germans prefer international humanitarian operations. Germans fret that the French have become warmongers, while many French see appeasement rather than remorse when today’s Germans pronounce: “Never again war, never again Auschwitz.”

In economics, Germany is a powerhouse of free-market liberalism, strong on austerity and scornful of budget profligacy, which Germans associate with “the Euro welfare state,” a very French idea.

The very definition of Euro-power is up for grabs: For the French, as they intervene in Africa and the Middle East, it is military and political. For the Germans, power is as much economic as it is political, with an eastward focus toward Russia and its neighbors.

Looking ahead, the most perilous clash may be over the flood of Muslim refugees and other migrants. Last year, Germany, acting solo, invited more than a million while France took in — reluctantly — a few thousand. France wants to shut the Continent’s borders, while Germany wants Turkey to help bring in more refugees — a clash not over conscience as much as competing economic imperatives. Germany requires more workers, since its native population is aging at a rate second only to Japan’s. France, by contrast, lives with enormous unemployment — and a birthrate among Europe’s highest.

France has also recognized that its greatest social challenge is to integrate millions of Muslim French citizens into its secular society — a crisis of identity for both. That type of tension is something Germans have not worried about nearly as much. As Joschka Fischer, a former foreign minister, wrote last year in Vanity Fair, “Angela Merkel governs a Germany where the sun shines every day, the dream of any politician democratically elected.”

Until a few weeks ago, that is. The horrific culture clash in Cologne on New Year’s Eve, between a mob of Arab immigrant men and groups of young German women whom they assaulted, was a wake-up moment for many Germans — a hint that they can’t remain forever a self-confident island in a sea of increasingly insecure neighbors. Yet Ms. Merkel still clings to Germany’s open door for immigrants, even though that stance now isolates her from her German constituents as well as the rest of Europe. It also prolongs Europe’s inability to find a unified approach to the problem, most recently last week in Brussels at a failed summit meeting on the subject.

Last fall, Ms. Merkel’s signature advice for Germans was “Wir schaffen das” — We’ll make it. But now she is missing an opportunity to listen more closely to her newly traumatized citizens and to the jittery rest of Europe and invite France to narrow the gulf between them. Surely, if they tried, these two partners could find some middle ground between ignoring a threat and refusing to help innocent victims.

But this has not been an auspicious time for such collaboration. Even though radical Islam, mass migrations, Russian revanchism and military interventions are challenges that no European state can meet alone, political sentiments across the Continent are all in the wrong direction. Frightened Europeans retreat into their sovereign little states, propelled by the popular right and xenophobia. In Hungary and Poland, those forces have taken power. By 2017, they may well do so in France, and Britons may have quit Europe altogether. That would leave no nation in a position to take the reins from France or Germany in leading Europe’s imperfect union.

So what comes next? Can we reasonably believe Europe will snap out of it? Will there be a Franco-German turnaround in shamed memory of the slaughter at Verdun 100 years ago? I don’t think so.

It is a matter of leadership. In the 1990s, François Mitterrand and Helmut Kohl, like Adenauer and De Gaulle before them, could work together, in part because they had experienced the ultimate alternative — the horrors of war. But those giants have long left the stage. There exists today neither any guiding program nor true solidarity, and historical memories have grown very short. Ms. Merkel and Mr. Hollande are more than ever focused on their own national conundrums: for France, how to control terrorism; for Germany, how to treat refugees.

What Europe’s heads of state have not done, and simply must begin to do, is prepare their citizens for the one great requirement for progress toward more unity — an enormous leap of faith and optimism, even while in the grip of fear. Instead, they betray their peoples’ fondest dreams by pecking at one another. And even my generation, who were 15 to 20 years old when the Berlin Wall fell, fails to stand up to them and demand that they save the dream we were promised — a Europe finally at permanent peace and working in unison after all the divisions and horrors of the 20th century.

Olivier Guez is a French essayist and a screenwriter for the film The People vs. Fritz Bauer. This essay was translated by Edward Gauvin from the French.