In late April, the #MeToo movement belatedly shook Venezuela’s cultural sphere. A wave of accusations and revelations by young women against prominent artists in the rock scene spread quickly to other sectors, including dance, journalism and acting. Soon, #YoTeCreoVzla (I believe you, Venezuela) started trending.

On April 29, the accusations reached Venezuela’s world-famous youth orchestra program, El Sistema. That day, a former El Sistema musician, Angie Cantero, posted a public story on Facebook, saying that El Sistema “was / is plagued by pedophiles, pederasts, and an untold number of people who have committed the crime of statutory rape”. Behind its attractive façade, she alleged, “there are a lot of disgusting people who love to deceive girls and teenagers, taking advantage of their position of power and renown within El Sistema”.

Cantero said she began receiving sexual propositions from adult male teachers when she was 13. She was able to resist them but said that “sadly, this wasn’t the case for many of my friends, who were also underage at the time, and they ended up involved in relationships (which included sex, of course) with these guys who were much older than them”.

Her story, soon shared more than a thousand times, generated hundreds of comments that supported her depiction of El Sistema. Some people recounted firsthand experiences; others recalled frequently hearing about such behaviors. One woman described being raped by a teacher when she was 14. Cantero’s courageous disclosure has since sparked a collective portrait of teenage girls in El Sistema being systematically groomed by older male teachers, with coercive innuendos and propositions as everyday occurrences.

We turned to several women for corroboration. They asked that their real names not be used for fear of potential retaliation and professional repercussions. Lucía, a member of El Sistema for 18 years, told us that predatory behaviors had long been evident in the program. “There were many cases that came to light, but it was the girls who paid the consequences. The role of the teachers was swept under the rug”, she said.

María, who spent 15 years in the program, noted that sexualized grooming was so ordinary and unchallenged that most girls might not have even perceived it as predatory and abusive in the moment. Or, as one of Cantero’s respondents put it: “I can identify with all these testimonies. How crazy to think that we somehow ended up normalizing what went on and continues to go on”.

Except, of course, it’s not “crazy” at all. Systems of abuse warp victims’ sense of reality. They can cause vulnerable individuals, especially children, to confuse what is right and wrong, to mistake predation for affection.

El Sistema musicians have further alleged that some male figures of authority traded musical benefits (tours, intensive courses, promotions) for sex. Such abusive behavior, they said, has long been “un secreto a voces” — an open secret.

Geoff Baker outlined the problems of sexual harassment and abuse in his 2014 book on El Sistema. The organization responded by saying that allegations of widespread abuse were “absolutely false”. This new wave of accusations, louder than ever, suggests otherwise.

Indeed, former El Sistema violinist Luigi Mazzocchi affirmed that teacher-student relationships were “the norm”. In a 2016 VAN magazine article, Mazzocchi recalled: “Some of the ... teachers would actually say it out loud: ‘I do this [have sexual relationships] with my students because I think we’re actually helping them become better musicians, better violinists.’ ”

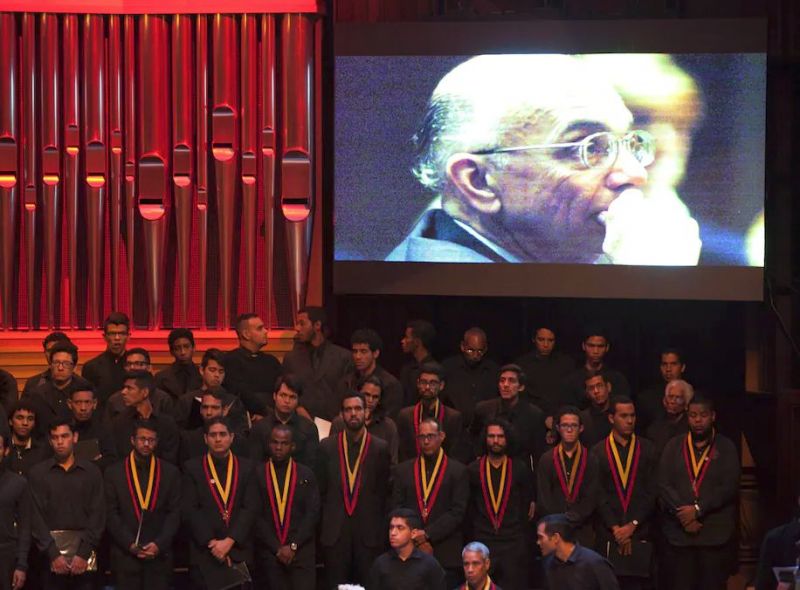

The recent #YoTeCreoVzla movement emboldened one of our contacts, Lisa, to go public with a harrowing, in-depth story of the sexual abuse she said she suffered at the hands of two El Sistema oboe teachers. It started when she was 12. She paints a searing account of chronic abuse juxtaposed against extraordinary musical opportunities, the latter of which included a 2010 concert with the National Children’s Symphony Orchestra of Venezuela led by Berlin Philharmonic conductor Sir Simon Rattle.

Echoing Mazzocchi, Lisa explains how her teacher provided artistic justifications for his behavior. “His methods rested on an uplifting discourse of art, passion and intellect”, she says. “According to him, I had to let myself be carried away by sexual desire in order to achieve a full sound”.

These revelations have massive ramifications. Hundreds of music education programs across dozens of countries fly under the banner of “El Sistema”. It is central to the brand of world-famous Venezuelan conductor Gustavo Dudamel, the music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

Venezuela’s political and economic crisis has forced many El Sistema musicians to leave the country, and they can now be found in music education programs around the world.

To be sure, this is not merely a Venezuelan problem. “Open secret” is how New Yorkers, Chicagoans and classical musicians at large characterized the predatory actions of the late conductor James Levine. “Open secret” is how people have retrospectively described the patterns of emotional and sexual abuse within various music schools and conservatories, such as Chetham’s, Curtis and Berklee.

What will it take for El Sistema to acknowledge its problems and commit to reparative actions? Can programs continue to wear the “Sistema” badge with pride? What should be the response of UNICEF, the United Nations agency for the defense of children’s rights, for which El Sistema has been a goodwill ambassador since 2004?

Some people might argue that El Sistema does more good than harm. But such claims will always be flimsy as long as the harm isn’t properly investigated.

One thing is clear. Waiting for this ongoing crisis to blow over yet again — waiting for survivors to fall silent, for the news cycle to refresh — is indefensible. El Sistema’s “open secret” is, it’s safe to say, a secret no longer. Is the world finally willing to listen?

Geoff Baker is professor of music at Royal Holloway, University of London, and the author of “El Sistema: Orchestrating Venezuela’s Youth”.

William Cheng is chair and associate professor of music at Dartmouth College, and the author of “Loving Music Till It Hurts”.