The gun attack in Dallas, Texas, at a contest to draw cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad, evokes memories of the January shootings at the Paris office of the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo.

Two gunmen were killed and a security guard injured at the Muhammad Art Exhibit, organised this weekend by the American Freedom Defense Initiative. Coincidentally, the French magazine will pick up a Freedom of Expression Courage honour in New York tomorrow, awarded by the literary group PEN. When six writers pulled out of the ceremony in protest, Salman Rushdie accused them of cowardice and condoning terrorism. The six argue that the award validates “selectively offensive” racist and anti-Islamic material. All parties rightly agree that no one anywhere should be threatened or harmed for what they write or draw.

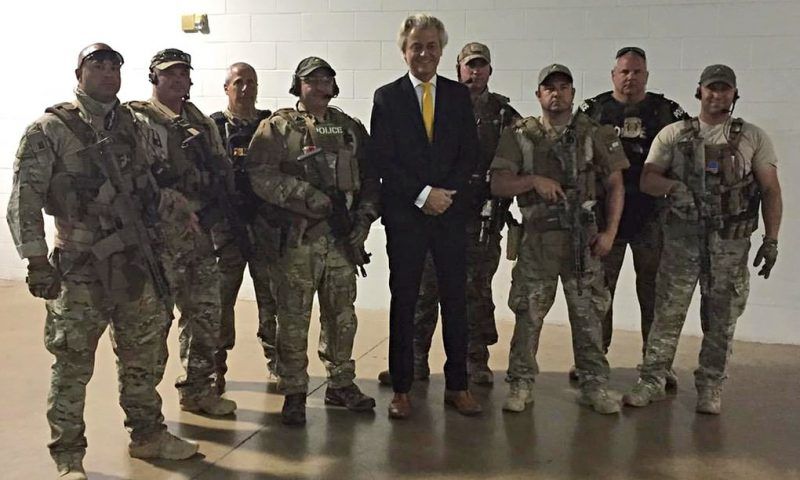

But are all victims of this contemptible violence automatically courageous? To insist that this is so, as PEN appears to be doing in honouring Charlie Hebdo for “soldiering on”, paradoxically allows the actions of the criminally violent, whatever cause they claim, to determine what constitutes brave and significant speech. Are Draw the Prophet contests – organised in this instance by the virulent anti-Islamic campaigner Pamela Geller and attended by the far-right Dutch politician Geert Wilders – really the sort of thing for which we defend the hard-won right to speak difficult truths?

The time has come for a more challenging conversation about what makes for the really courageous and truly oppositional. Outcries about free speech that revolve solely around western controversialists and unhinged gunmen declaring insult threaten to narrow our understanding of its value; we are in danger of thinking of all offending speech as brave speech. Without giving quarter to violence even against pubescent graffiti, we must ask what sorts of speech make the defence of freedom of expression truly worthwhile.

Free speech is most precious when it genuinely questions power, when dissent challenges and undermines an unacceptable status quo. Meaningful dissent makes the invisible visible. While the openly tyrannical are obvious targets, in formally democratic contexts free speech is truly only a weapon when it sets its sights upon insidious norms and received ideas rather than sanctioned enemies. Charlie Hebdo is frequently described as satire against the powerful, but power is always context-specific. What is the oppositional value of caricaturing religion in a formally secular nation, particularly if the targeted faith is that of a demonised minority who are often pilloried as enemies of the state anyway?

By contrast, it was breathtakingly brave of the Saudi blogger Raif Badawi to criticise a vicious religious-political regime. Publicly flogged and still in jail, Badawi continues to pay a heavy price. Meanwhile the governments of “free” western countries continue to parley with Saudi autocrats.

The Bahraini human rights campaigner Nabeel Rajab is back in prison, and on the day that his detention was extended the British defence secretary, Philip Hammond, secretly visited the repressive regime to which Britain wants to sell BAE aircraft. Funnily enough, formally secular and formally theocratic countries can share the same largely unquestioned faith: the “sacred hunger” of making large profits.

Criticism, like charity, shouldn’t be parochial, but it does well to begin at home. It’s far easier to attack “them” than examine the deceit, delusions and cultural certainties that constitute “us” – whether by acknowledging the depredations of the British empire or exposing its legacy of structural racism. To be brave is to speak up relentlessly against the austerity consensus across the political classes, and for the poor, disabled people, asylum seekers, working class migrants: all at the sharp edge of neoliberal economic tyranny.

Neoliberalism has itself cannily narrowed of the idea of “freedom” to consumer choice and the right to offend; instead we should be talking about the right to freedom from exploitation, illness and hunger. Meanwhile, in ostensibly liberal spaces like British and American universities, conferences on Israel and international law are cancelled under blatant political pressure, and academics who condemn war crimes in Palestine are fired.

Murder is only one way to silence people and causes; it’s far easier and more effective to turn them into caricatures (“the loony left”, “welfare dependents”, “feminazis”). Easier still to allow them minimal speaking space, since the media is still largely run by half a dozen powerful interests while peddling cant about “our way of life”. As migrants drown in the Mediterranean, the insidiously bland phrase routinely used by newscasters – “Europe’s migrant problem”– shows how mainstream thought can veer towards the far-right.

Be it Dallas or Paris, the tasteless joke is not the same thing as the unpalatable truth. The latter is rarer, more challenging and harder to disseminate, never mind celebrate. This confusion has serious ramifications: much energy is expended on the mawkish self-pity of elite literati while the resistance of the under-represented – who often live in continuous danger – remains invisible. It’s time to celebrate the courage of the genuinely adversarial, those who challenge both cultural certainties and the wilful infliction of adversity across the world.

Priyamvada Gopal teaches in the Faculty of English at the University of Cambridge.