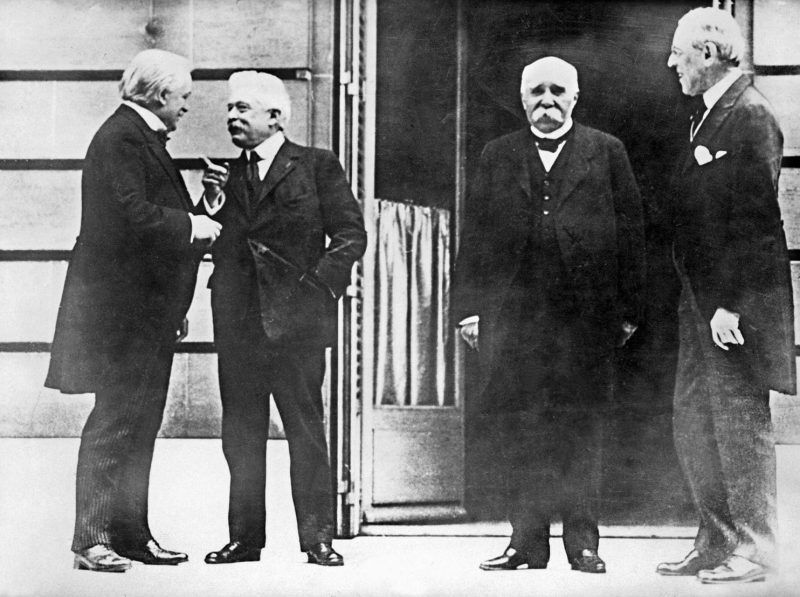

June 28, 2019, marks the centenary of the Treaty of Versailles, which formally ended World War I. The major parties to the war negotiated among themselves to resolve the issues under dispute, making Versailles a classic peace treaty.

As such, it’s now an endangered species, as my research on peace treaties explains.

Soldiers and civilians alike cheered the Nov. 11, 1918, armistice and subsequent treaty. But historians have frequently disparaged the Treaty of Versailles — and its infamous war reparations clause, which some experts maintain was a cause of World War II. The United States abstained from signing this treaty. The United States also did not join the League of Nations, the international dispute resolution forum conceived by President Woodrow Wilson — another factor that may have hindered the treaty’s efficacy. But for all of Versailles’ problems, it represented a clear end to a major war in a way that we rarely see today.

Wars used to end in peace treaties — but that became less common

From 1816 to 1919, formal peace agreements marked the conclusion of nearly three-quarters of wars between countries. Since 1919, that percentage has dropped precipitously, to about one-third. The Iran-Iraq War of the 1980s, the 1982 Falklands War and the 1991 Gulf War did not end with peace treaties that included the major parties as signatories negotiating an agreement to end the fighting.

The U.N. Security Council passed resolutions to conclude the Iran-Iraq and First Gulf Wars, but such resolutions have been relatively few and do not substitute for peace treaties. Security Council members negotiate these resolutions; these are not agreements negotiated and signed by the major belligerents.

Not having a peace treaty matters … for peace

Why is this distinction important? Not having a peace treaty can delay troop withdrawals, as well as the normalization of relations between former enemies. Russia and Japan, for example, did not normalize relations until decades after World War II because they had not signed a peace treaty.

But the most important effect of peace treaties is that, well, they can bring peace. Even accounting for the possibility that peace treaties may be easier to conclude in some conflicts than others, interstate wars that end with formal peace agreements tend to see years more peace than wars that end without peace treaties.

India and Pakistan, for instance, have fought three major wars over Kashmir since India’s independence in 1947, but only signed one formal peace treaty to conclude the 1972 Bangladeshi war of independence. While cease-fires or truces punctuated two of the other wars, India and Pakistan have never managed to conclude a formal peace treaty resolving the Kashmir issue. In contrast, Israel and Egypt signed the Camp David Accords in 1979. Before Camp David, the two countries had fought several major wars. Since Camp David, they have not fought each other directly.

Why don’t countries formalize peace with a peace treaty?

Several changes since the Treaty of Versailles have upended the traditional role of peace treaties.

First, there has been a proliferation of laws of war governing belligerent conduct during conflict — this leaves countries with less incentive to conclude formal peace treaties to end wars with other countries. Peace treaties represent an opportunity to hold belligerents to account for any violations of the laws of war. But as these laws have increased in number, countries become more reluctant to leave themselves vulnerable to such accounting.

Here’s an example: Russian soldiers removed thousands of cultural objects from Germany during World War II. But Russia and Germany never signed a peace treaty after the war, which leaves the status of these objects in international legal limbo — and this legal ambiguity helps bolster both Germany’s efforts to reclaim these objects, and Russia’s argument that it has a right to keep them as restitution.

Second, a focus on international mediation by organizations like the United Nations has effectively created a supply of peacemakers. And because most wars in the U.N. era are civil wars, this increase has produced a clear rise in the use of peace treaties to end civil wars — in contrast to the decline of peace treaties in wars between countries.

In fact, I found that approximately 10 percent of civil wars ended with formal peace treaties in the 19th and early 20th centuries, but this percent has nearly tripled since the founding of the United Nations. Georgetown scholars Lise Morjé Howard and Alexandra Stark note a similar increase in the use of peace treaties in civil war.

But third, and related, as recent research suggests, peace is most likely when there is buy-in from local groups and parties. We see the role of these local parties most clearly in the context of civil war peace treaties. While wars between countries that end with peace treaties see an average of four more years of peace, civil wars ending with peace treaties see about three fewer years of peace. This difference is partly due to the challenges of securing peace among belligerents who cannot retreat behind international borders but it may also reflect the difficulties external mediators face in understanding local dynamics in these conflicts.

Peace treaties may be staging a comeback — but they won’t look like Versailles

Recent events have brought peace treaties back into the limelight, however. Last year, after two decades of fighting, Ethiopia and Eritrea signed a peace agreement. And one of the “carrots” the Trump administration is using to bring North Korea to the nuclear negotiating table is the possibility of a peace treaty that would officially end the Korean War. The U.S. has also floated the notion of a peace treaty with the Taliban.

In the past, peace treaties to end wars typically involved parties that viewed each other as equals under international law, if not in terms of military power. But peace agreements today involve rebel groups and central governments, former secessionist movements and the nations from which they seceded, and both major powers and nonstate parties.

To some extent, this asymmetry reflects the landscape of current conflicts around the world. But it also raises an important question: 100 years after the Treaty of Versailles, is the very nature — and not just the number — of peace treaties changing?

Tanisha M. Fazal is associate professor of political science at the University of Minnesota. Her most recent book is “Wars of Law: Unintended Consequences in the Regulation of Armed Conflict” (Cornell University Press, 2018).