On March 22, a tweet appeared on my timeline featuring a photo that read, in Spanish: “Dear clients, we want to inform you that we will be here working until coronavirus kills us.” The scene behind and around the words was familiar; it could be almost any neighborhood market in Mexico.

Immediately I felt a pang of guilt and worry. I live in Mexico City and hadn’t been to my local market, Mercado La Dalia, in weeks — fear of the virus (and the privilege of having a small stockpile of canned and frozen foods) kept me in my apartment. (On Friday, Mexico had more than 6,800 confirmed cases of covid-19 and more than 500 deaths.)

But the tweet reminded me that I was part of the problem, that I was one in a sea of customers likely going to the market far less. I put on a mask and gloves, suiting up to go buy some kiwis and avocados, to talk to the people still working in the stalls and keeping this corner of the city fed.

I have no right to claim that anything is truly “mine” in Mexico. I’m a foreigner who moved here to be with my now-husband, who clumsily learned Spanish and more clumsily still learned how to survive in this colossal metro area of 21.5 million. But the words still slip from my mouth: “Well, at my market … ”

A local market in Mexico City is an entirely different shopping experience from the grocery stores I grew up in the United States. Stands run through tall, spacious buildings, overflowing with produce, dried peppers and spices, meats, dairy, candles, piñatas, cleaning products, dog food. There are also breakfast spots and taco stands, each with its own specialty: carnitas, cabeza, suadero. Sellers offer many of the same products, but loyalty goes a long way. I have my chicken lady, and I am her chicken customer. I have my flower guy, and I’m the woman who can never remember any of the names of his flowers but buys them anyway.

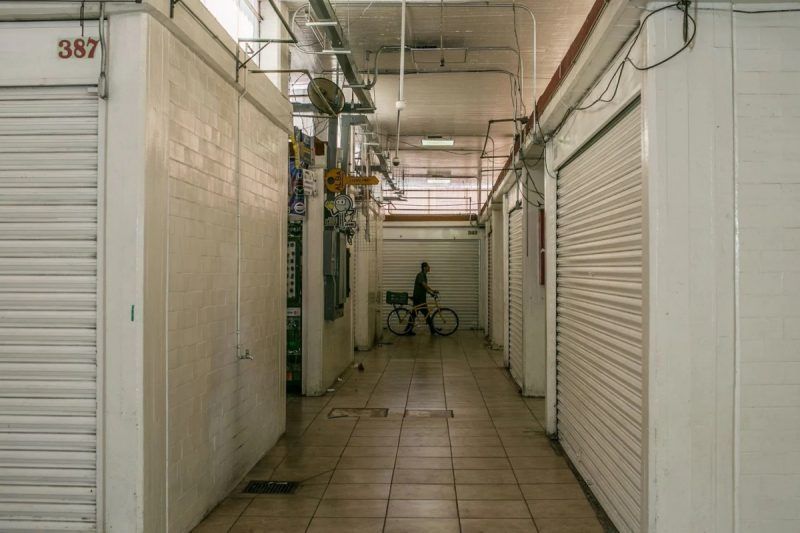

When I walked into Mercado La Dalia, just a few blocks from my apartment, I noticed the closures immediately. The halls were quieter. Stalls were covered in sheets or tarps. Benjamín, my flower guy, was gone, his stall also covered.

The people who work in the markets are members of Mexico’s informal economy, which makes up about 30 percent of Mexico’s gross domestic product. Workers in the informal economy face greater economic uncertainty and receive fewer (if any) protections. They also run a higher risk of contracting the virus, given that they cannot take paid time off work and many of their jobs — garbage collectors, street vendors, cleaning staff, delivery personnel — are essential.

On Friday, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador announced a $2.5 billion stimulus package to mitigate the effects of the pandemic, but he offered no details on how the money will be distributed. A loan program for small businesses will be set up through the Social Security Institute (ISSSTE), though it is so far unclear how much money those in the informal economy will be able to borrow.

People in La Dalia didn’t seem hopeful. Almost everyone I talked to mentioned a dip in customers. “I’ve never seen the market like this, never,” said Veronica Mora, “and I’ve worked here for 30 years.” She cuts raw chicken (on days when I am not working, I am proudly her chicken customer) with scissors and fusses with her face mask. “We sell food here, people need food. So we haven’t been affected so badly, but we will be affected. I am sure of it.”

One thing that doesn’t scare many: the virus itself. I heard a variety of theories ranging from religious proclamations of protection to the idea that if you eat healthy and exercise, the virus can’t really hurt you.

I walked laps around the market and saw the majority of vendors wearing masks, though some with the mask looped around their chin or covering just their mouth. It was near-impossible to maintain six feet between people, and it seemed as though most people weren’t invested in the effort. A few days ago, the market put restrictions on the number of people who can enter. Benjamín López, who has worked in the market for 27 years, said he wears his face mask when he leaves the market but doesn’t need it here. “People are really afraid. I think what they need more than anything is information, real information.”

As Mexico’s president continues to face criticism over his slow initial response and dismissive attitude, the country’s health official taking the lead on covid-19 recently said that the country likely has eight times as many cases of coronavirus than are being reported. Public hospitals are already facing shortages of personal protective equipment. And even Mexico’s $17 billion medical device industry ramps up production of ventilator components and hospital beds, very few will stay behind — López Obrador acknowledged recently that there were only 5,000 ventilators in the country.

The products, manufactured largely in factories run by U.S. corporations, will land in almost every hospital in the United States. Very few will remain in Mexico

In La Dalia, Javier Sánchez shaved corn off the cob. At the stall he runs with his brother Juan, there is no talk of virus phases or strain on the public health-care system. Neither expresses personal concern about the virus, but Juan says their elderly mother is worried about them and is asking God to protect her sons each day.

“There is really no other way for us,” Juan said. “So we are here. Until we are shut down, we are here. Maybe we’ll see you again soon?”

Meghan Dhaliwal is a photojournalist based in Mexico City.