Gathered in Rome last week to discuss marriage, divorce and the widening array of domestic arrangements with which they now must contend, a group of Roman Catholic bishops released a statement that included a theological turn of phrase that proved more telling than intended. “We must not forget that the church that preaches about the family is a sign of contradiction.”

This was not meant as a self-aware nod to the incongruity of a cohort of celibate men discussing the place of birth control, child-rearing and marital relations in the lives of millions of noncelibate Catholics, nor as an acknowledgment that the church has held conflicting views on the family from the beginning. A “sign of contradiction” here alludes to a prophecy given to Mary early in the Gospel of Luke that the infant Jesus would be a “sign that is spoken against” by the people he had come to save.

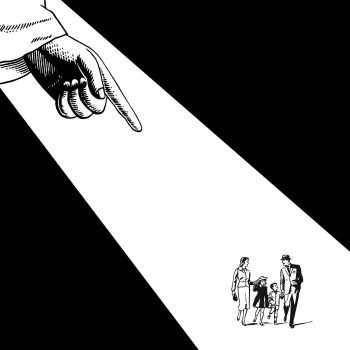

For Christians, this sign is a call to stand apart from society, enduring scorn for the sake of religious truth. Referring to their synod on the family this way, the bishops were not humbly admitting their inability to speak from experience, but making a lofty claim to a higher authority.

For Christians, this sign is a call to stand apart from society, enduring scorn for the sake of religious truth. Referring to their synod on the family this way, the bishops were not humbly admitting their inability to speak from experience, but making a lofty claim to a higher authority.

Still, the contradictions most evident in the aftermath of the bishops’ statement were those within their own ranks. A recap of discussions held during the first half of a two-week meeting convened by Pope Francis, the report was greeted with outsize praise and alarm for its willingness to engage in unexpected ways with issues including homosexuality and what the church used to call “living in sin.”

Within hours of the Hungarian Cardinal Peter Erdo’s affirmation in the prepared statement that “cultural and socio-economic factors” may influence the choice to begin, delay or end a marriage, and that same-sex unions could provide “precious support in the life of the partners,” other high-ranking clergymen stepped forward to claim that the media’s focus on such sentiments was “manipulating” the synod’s words.

“The message has gone out that this is what the synod is saying, this is what the Catholic Church is saying,” Cardinal Wilfrid Fox Napier of South Africa, who participated in the meetings, complained. “It’s not what we’re saying at all.”

Such disagreement was perhaps to be expected. The statement read by Cardinal Erdo was a relatio post disceptationem, a “report after debate” that attempted to wrangle a week’s worth of competing positions into a seamless account of continuing deliberations. Almost immediately, commentary on the document walked back the very statements that earned it such unanticipated attention.

In another sign of the synod’s internal contradictions, the Vatican released a new translation of the report three days after the uproar that greeted its original release. A section titled “Welcoming homosexual persons” became the entirely less welcoming “Providing for homosexual persons” and “partners” in same-sex unions became “these persons.” This last was a particularly puzzling rendering given that the phrase originally translated as “life of the partners” appears as “la vita dei partners” in the synod’s official Italian text.

Yet even if the effects of the “pastoral earthquake” described by one longtime Vatican correspondent turn out to be as lasting as the wall-shaking rumble of a passing diesel truck, something undeniably significant did happen at the synod last week. More than just a momentary softening of rhetoric, it was an indication that the idea of family is again evolving in Rome.

While Catholic defenders of traditional marriage may act as if family life has always been the highest good in the church’s eyes, for much of its history marriage was plainly seen as a lesser path to holiness. Just as the bishops’ report noted that “unions between people of the same sex cannot be considered on the same footing as matrimony between man and woman,” much the same was said for centuries regarding the difference between marriage and the consecrated virginal state.

Marriage was messy, full of situations regarded as unpleasant by the saintly, and bound up in cultural conditions that shifted over time. In the fourth century, Saint Jerome wrote that he valued marriage only because it produced potential virgins. Throughout the Middle Ages, manuals for confessors noted the many ways in which relations between husbands and wives could be deemed immoral.

At the 16th-century Council of Trent, when matrimony formally became a sacrament of the church, bishops weighed in on the pressing marital issues of their day by reflecting on the performance of nuptials in the cases of “vagrants” (best to be avoided), kidnapped brides (only after a released abductee gave her consent “in a safe and free place” could the church sanction such a union), and priests (if anyone says they can marry, the council canons warn, “let him be anathema”).

In every instance, the question of who might constitute a family was a matter of how far those involved fell short of an unattainable ideal.

Which is perhaps not so far from the supposedly “wounded” and “irregular” families that are largely the focus of the synod’s report: the divorced, the remarried, the cohabitating; the two-faith marriages, the two-mother households, the two grooms who walked down the aisle. By including those long regarded by the church as beyond the bounds of Catholic propriety within their discussion of family as the “school of humanity” that is a “source of joys and trials,” the synod’s bishops have not opened a big tent welcoming all those mentioned to fully participate in the life of the Catholic Church, and indeed they are unlikely to do so.

Yet even quibbling over words of qualified welcome, they have reminded the faithful that their church has developed over time through conflict and contradiction, and may again.

What family is not wounded? As Cardinal Erdo read the bishops’ relatio in a Vatican conference hall last week, anyone watching carefully could see on the desk before him a small sculpture of the holy family: Mary, Joseph and Jesus. To Catholics it is a depiction of a woman who conceived a child before she was married, a chaste stepfather who nearly divorced her as a result, and that original sign of contradiction, the human son of God. A church that claims to descend from this most untraditional of domestic arrangements might ask itself: Was any family ever more irregular than that?

Peter Manseau is the author of the forthcoming book One Nation, Under Gods: A New American History.