Jair Bolsonaro, an ultraright wing populist, was elected president on Sunday. As I processed this new reality, I looked out my window and watched the celebratory fireworks illuminate the night sky. In the distance, I made out one of Mr. Bolsonaro's supporters holding up a sign that said, “Ustra Lives.”

It was a chilling reminder of our past. From 1970 to 1974, Carlos Alberto Brilhante Ustra was the head of the DOI-CODI, the intelligence agency responsible for stamping out critics during military rule. He oversaw the torture of political dissidents while they were detained by the secret police.

Mr. Bolsonaro’s rise has been driven by people’s anger and disillusionment, stemming from a huge multiyear corruption probe that has upended the country, a homicide rate that is sky high and a flailing economy. It didn’t matter to many that his inflammatory rhetoric denigrated women, as well as gay, black and indigenous people, or that he spoke fondly of torture and dictatorships. Indeed, an estimated 43 percent of the population is in favor of the military intervening in government affairs. I think Brazilians have forgotten what it means to be ruled at gunpoint.

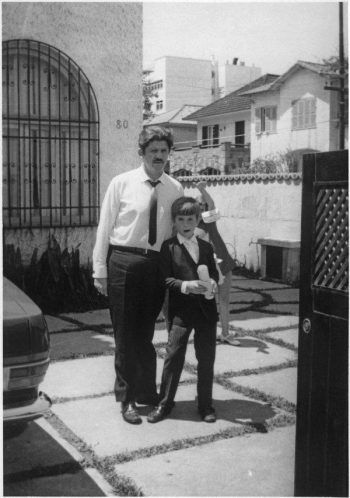

My father was a congressman for the State of São Paulo and a socialist. The military junta revoked his mandate after the 1964 coup d’état, and he went back to work as a civil engineer. I was 11 when he was arrested, along with my mother and my sister. It was a sunny morning in January in Rio de Janeiro in 1971, and we were getting ready to go to Leblon beach, which was across the street from our house. Suddenly, six armed men dressed in plain clothes entered through the back door into the kitchen, pointing machine guns. Outside, more men surrounded the house.

The government had intercepted letters and documents from leftist organizations that were sent to my father from dissidents in Chile. They thought he had a role in organizing the distribution of mail and information for exiles in Brazil and out of the country. On that day in 1971, my parents were in their swimsuits when the armed men burst into the kitchen. They took my father upstairs so he could get dressed while we all sat on the couch in the living room. He was told that the agents waiting outside were going to take him so that he could give his testimony. We never saw him again.

The six men stayed with us for the next 24 hours. Then they took my mother, Eunice, and my sister Eliana, who was 15 years old at the time, to the DOI-CODI facility in Rio de Janeiro, inside the Army headquarters on Barão de Mesquita Street. My other sisters, Ana Lucia, 13, and Beatriz, 10, and I were left behind alone.

My sister and my mother were harassed and intimidated. They sat hooded for 24 hours, without food or water. A speaker was blaring “Jesus Cristo,” a song by Roberto Carlos, over the screams of a man being tortured — most likely my father. My sister was released the next day. But my mother spent 12 days in a dark cell, wearing the same clothes she had on the day she was arrested. She was awakened at night by screaming guards, who would force her to look through pictures of wanted women and men. Thank you, military, for not killing her.

Over the years, we heard rumors about what happened to my father; that he had been killed while being tortured, that his body had been cut up into pieces. But it wasn’t until 2014, when former agents and officers who witnessed his torture testified to the Public Prosecutor’s Office, that we finally had an official account of what happened.

He was taken to DOI-CODI in Rio de Janeiro, where he was tortured. He died less than 48 hours after he was arrested. The prosecutor said the military’s intention was to “inflict acute physical and mental suffering, in order to intimidate him and obtain information about the recipients of the letters and documents that were sent to him.” A former army colonel, Paulo Malhães, said that he received an army order in 1973 to dig up and dispose of my father’s remains. We’ll never know what he did with them. I never did understand why my sister and my mother were also arrested. To be tortured with him, if he did not speak?

After the dictatorship ended in 1988, a new Brazilian Constitution, known as the Citizen Constitution, was approved. It afforded territorial rights to indigenous peoples and the quilombolas, who are the descendants of Afro-Brazilian slaves. It also extended protections to other minorities, and condemned “prejudice of origin, race, sex, color, age and any other forms of discrimination.” But now Brazil seems poised to return to its dark past.

In the lead-up to this election, there’s been an increase in violence and homophobia fueled by Mr. Bolsonaro’s misogynistic, racist, anti-L.G.B.T and anti-democratic views. The Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism registered more than 130 cases of violence against journalists in 2018. Swastikas have been painted on walls all over the city. Grindr, the world’s largest social networking app for gay men, sent an in-app safety reminder message to Brazilian users that said: “Following the recent election, members of the Grindr community raised concerns about the increased risk of violence. Take the necessary steps to stay safe this week.”

From the dictatorship we learned the importance of democracy, tolerance and the rule of law. Brazilians should not be fooled, Mr. Bolsonaro is not the savior our country needs. I thought that the life of my father and the suffering of my family and of many others was an essential chapter to help Brazil reflect and evolve. We never imagined that our struggle and pain would serve no purpose. That our struggle for the right to vote would be used to turn everything back. Pray for us.

Marcelo Paiva is a writer and columnist for the newspaper O Estado de S. Paulo.