A light for Congo’s democracy went dark this week.

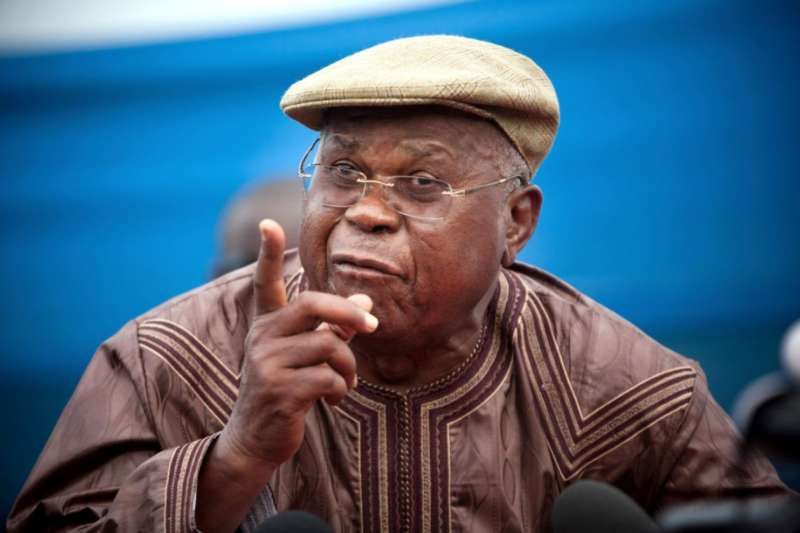

Etienne Tshisekedi, the 84-year old long-time opposition leader and force for political openness in Congo, died Wednesday in a hospital in Brussels, after suffering from a long-standing illness. Nicknamed the “Sphinx of Limete”, the former member of Patrice Lumumba’s post-independence government served four times as prime minister. Tshisekedi fought against the kleptocratic regime of Mobutu Sese Seko and resisted the governments of Laurent Kabila and his son, current president Joseph Kabila. Tshisekedi ran against Joseph Kabila in the flawed 2011 elections and lost. He never recognized Kabila as Congo’s true leader.

Since its independence from Belgium in 1960, Congo has never seen a peaceful transfer of power. Tshisekedi’s death stands to plunge Congo’s hopes for multi-party democracy further out of reach.

A Dec. 31 deal, brokered by the powerful Congolese Catholic Church (CENCO), would have seen Kabila step down this year after the organizing of elections. The agreement (known as the CENCO deal) was already on shaky ground in January; the notoriously reclusive Kabila, whose term expired in December, has not signed the deal, nor has he said publicly whether he will leave office. Tshisekedi was a key part of the CENCO deal, as he was to head an oversight committee in charge of monitoring the implementation of the agreement. The deal is likely functionally dead at this juncture — the opposition has called for suspending talks until Tshisekedi’s funeral.

There doesn’t look to be anyone who could fill Tshisekedi’s place in Congolese politics. Moise Katumbi, a wealthy businessman and former governor of the mineral-rich Katanga province, is a prominent opposition figure, but he has remained in exile outside of the Congo since the Kabila government issued a warrant for his arrest in May. It remains to be seen if Katumbi will return to the country anytime soon. Arguably, the only other force in Congo that commands as much respect and credibility is the Catholic Church, which has a long history of organizing grass-roots resistance against autocratic regimes. “The Catholic Church-mediated dialogue gained legitimacy in large part due to Tshisekedi’s blessing and the participation of his political party, the UDPS”, said Ida Sawyer, the Central Africa director and researcher for Congo for Human Rights Watch.

With the political deal on life support, and a lack of unifying political figures, the Congolese people are the first and last hope for putting pressure on Kabila. But with Tsisekedi’s passing, pro-democracy forces will likely have an exponentially more difficult time catalyzing the Congolese to go out into the streets. While Tshisekedi did not have many allies in Washington due to his hot-headed temperament, he enjoyed enormous popular support in Congo, particularly in Kinshasa. In July hundreds of thousands of Congolese people filled the streets of Kinshasa to welcome Tshisekedi back to the country after two years of medical treatment. “Despite his age and deteriorating health, it was largely thanks to Tshisekedi’s leadership and willingness to ally with others that the opposition remained somewhat and unusually united in their 2016 struggle against Kabila”, said Sawyer. Still, with a tanking economy, and day to day life becoming harder for ordinary Congolese, the potential for a popular uprising shouldn’t be counted out.

Ultimately, while the media-shy Kabila shuts himself off in his mansion in Kinshasa — reportedly enjoying his video games — the big question remains: Will his party organize elections this year at all? It looks unlikely. Last year, Kabila’s government claimed that it needed more time and money to organize voting in the mineral rich, infrastructure-poor country of 67 million, a move seen by many Congolese as part of the “glissment”, or slide, meant to keep Kabila in power as long as possible. It would be unsurprising if the regime claims that in the aftermath of Tsishekedi’s death that it needs time and resources to bring peace and order to the country before staging elections. And there may not be pressure from regional leaders, either. Already, Uganda’s foreign minister told Reuters that “there might be a need to examine the whole time agreement”, and that Tshisekedi’s death “might cause some ripples and a shaking of the system, hence the need for Kabila to continue holding the country together until such time as things stabilize”.

The United States last year spent considerable time and effort trying to pressure Kabila and his government to organize elections and to respect the constitution. The Obama administration imposed sanctions on key members of Kabila’s party and spilled a decent amount of diplomatic ink on statements condemning state violence against protesters and urging adherence to democratic norms. By all measures, democracy promotion does not seem to be a priority for the Trump administration right now, much less African democracy. Surely Kabila knows he will not face the same amount of pressure from Washington anytime soon. For now, Kabila looks content to play games with the future of Congo — and it doesn’t look like anything or anyone will stop him.

Karen Attiah is The Washington Post's Global Opinions Editor.