At the height of pandemic restrictions in Mexico last year, Lorena Romero’s employer halved her hours — and the single mother of two is still struggling to get her working life back on track.

At the height of pandemic restrictions in Mexico last year, Lorena Romero’s employer halved her hours — and the single mother of two is still struggling to get her working life back on track.

Romero wants to step up her hours and has looked at various roles — including live-in domestic work positions about two hours from her house. But the need to look after her teenage children, who have not yet returned to school full-time, makes it hard to find suitable opportunities.

“I can’t take that kind of work right now; I need to be close to my kids . . . It’s been difficult,” said the 35-year-old from Mexico City.

Romero’s predicament echoes that of tens of millions of women during the pandemic. As female-dominated service sectors such as retail and domestic care were hit by lockdowns, many women lost their jobs. Many others stopped work or reduced their hours in order to cope with domestic responsibilities that fell disproportionately on them.

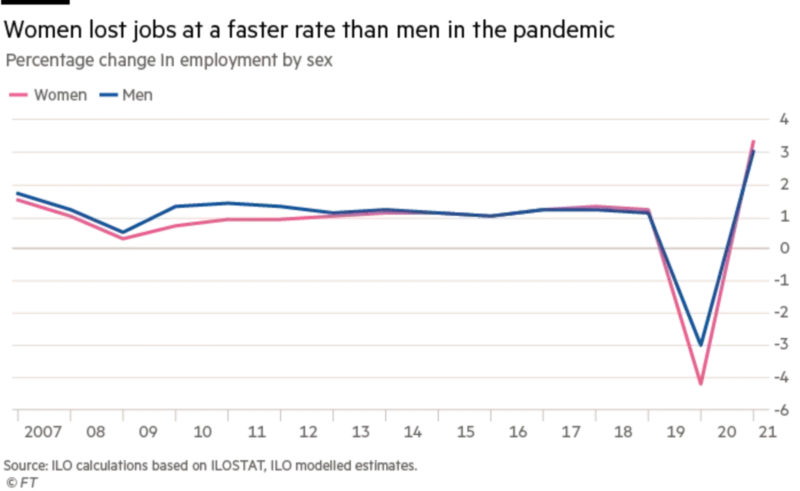

The Covid-related recession destroyed 4.2 per cent of women’s employment worldwide during the pandemic, compared with 3 per cent for men, according to the International Labour Organization, exacerbating a global gender gap where 43 per cent of working-age women are employed, versus 69 per cent of men.

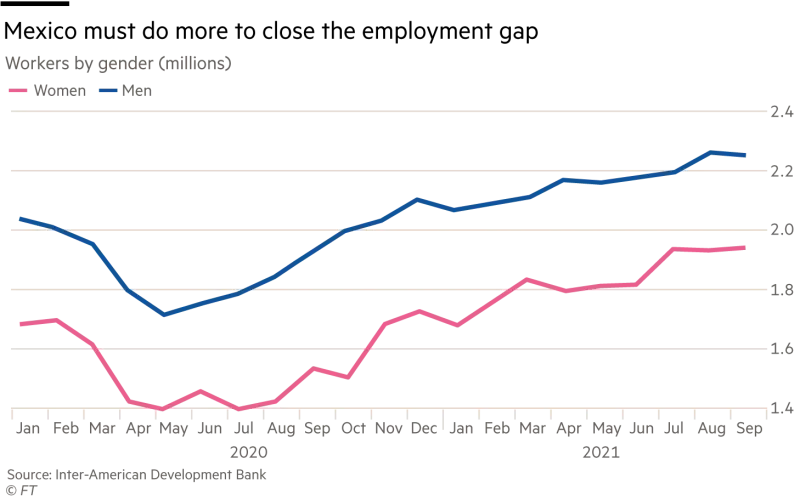

While the “she-cession” has all but ended in western countries and some regions such as Africa, its lingering effects are acute in Latin America.

There, women remain 2.6 times more likely than men to have lost their pre-pandemic jobs and many have left the labour market entirely, according to a forthcoming World Bank report. Female employment participation rates are now worse than before the pandemic in almost every country in the region.

Though cases are currently low, Mexico has had one of the highest pandemic excess death rates in the world and the economic recovery has been fragile.

“The recovery has been very much asymmetric and so the gaps have widened across the board,” said Ximena Del Carpio, who leads the World Bank’s poverty and equity practice group. “The women that have fared the worst in the region are mothers with young children.”

Outside the capital, Mexico’s vaccination campaign has been slow and just 50 per cent of the country’s population is fully vaccinated.

One factor that severely set back women in Latin America is that the region had some of the longest school closures in the world, according to Unesco. Making things harder still are social norms around childcare and housework.

On average, a Mexican woman working 40 hours a week will do over twice the amount of domestic work as a man with the same schedule, according to the statistics body INEGI.

The lack of a trusted and affordable market for childcare also means Mexican mothers rely heavily on grandmothers to take care of children. But Covid-19 made that feature of traditional family life more difficult.

“Most people here depend on the grandparents,” said Maribel Hernández, who works peeling prawns in the northern Mexican state of Tamaulipas. During the pandemic her ability to work depended on her parents looking after her son and disabled brother’s kids.

“If they [my parents] can help, I go out to work but if they can’t I have to stay behind,” she said, adding that day care centres were for mothers with higher-paid jobs than her own.

One study shows that when a Mexican grandmother dies in a three-generation household, the daughter’s probability of working drops by 12 percentage points.

“The issue of the system of care in Mexico is fundamental,” Edgar Vielma Orozco, director of socio-demographic statistics at INEGI, said about the reliance on grandmothers to provide childcare. “You shouldn’t depend on your mother to be in the labour market, there should be a care system.”

Argentina provides a severe example. Before the pandemic, about 1.2m women, or 17 per cent of the female workforce, were employed in domestic work.

But when Covid-19 struck, the capital Buenos Aires went through one of the world’s longest and strictest lockdowns, crippling the economy and destroying jobs as families feared getting sick. As a result, 350,000 domestic workers were still out of a job by this March, according to finance ministry data compiled for the women, genders and diversity ministry.

“For those who work in private homes, the job recovery rate is the slowest of any industry,” including hard hit sectors such as hospitality, said Mercedes D’Alessandro, an Argentine economist and director of gender and equality within the finance ministry.

To try to improve matters, the government has launched a programme of wage subsidies for cleaners and other domestic workers.

Critics say it only entrenches outdated gender roles, but the Argentine government hopes it will provide critical employment for thousands of women.

Beyond subsidies, other helpful policies for the region might be reskilling programmes, improved access to finance for women entrepreneurs and reliable childcare, Del Carpio said.

“The [childcare] services may be there but will you put your child in a centre that has no oversight? No,” she said.

For those women who can work from home, the rise of flexible working during the pandemic has been a bright spot. But for most Latin Americans that isn’t possible given the region’s relative paucity of white-collar jobs. As a result, the responsibilities of domestic care often take precedence over paid work.

For the likes of Leticia Velázquez, it’s a conundrum. In May she quit the Mexican textile factory job she had for more than two decades in the southwestern state of Oaxaca out of fear of getting Covid and giving it to her 84-year-old mother, who lives with her.

“We were seeing colleagues dying,” the 56-year-old said, adding that even if they wanted it, a care home for her mother was not an option. “It costs a lot of money that, frankly, I don’t have.”

Christine Murray and Lucinda Elliott.